Not to put too fine a point on it, almost all of Marcel Duchamp’s artworks from around 1900 onwards are centered around love, sex, and erotics: penetrations of various kinds, rhythmic pulsations, and sexuality and gender relations in respect of sexual activity or sexual longing. It is also well known that many of these works take as their character, at first glance, an almost schoolyard type of humor in this respect—L.H.O.O.Q. (1919) being a prime example.1 However, aside from the often funny or glib smutty façade of some of Duchamp’s works, his engagement with erotics and diagrammatics can be explored to elicit a truly strange, fascinating, and surprising dialectical methodology of rationalizing what in love, sex, and erotics are the most seemingly irrational of human experiences.

Duchamp’s works are born of a rare mix of avant-garde transgressive fervor (which has its own erotic charges of desire and violence), patient, highly-skilled and painstaking craftsmanship, and careful, methodical, scientific, and philosophical enquiry into what by contrast appears the least erotic of all methodologies, that is, mathematical geometry. His pieces may, again at first glance, seem very distant from the precision and dry procedurality of the algebra associated with geometrical projections and transformations in calculus, but I would argue that his own unique approach to image and object-making has its foundations in the erotics that he found in mathematical conceptions, projections, and formulations of n-dimensional space, and the penetration of chance into ordered systems.

Furthermore, Duchamp was also interested in how systems, or machines, produce and reproduce forms and images, and also ideas, in nonstandard ways. The complex forms of projective geometry and algebra that he studied whilst a librarian at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris, in 1913, as well as the philosophical texts that he read on concepts of multi-dimensional space gave him key tools to be able to think of and produce artworks that we can now recognize or categorize as ‘nonstandard series’2—a term today more typically associated with digital electronic fabrication technologies and parametrical scripting softwares. However, as a key example, it would be apparently absurd to conceive of The Large Glass (1915–1923) and Étant donnés (1946–66) as a series (as Duchamp does, in fact) without considering them a nonstandard series (as I do), because their forms are so very different, albeit that their component parts are given the same names by Duchamp. In the context of Duchamp’s avowed interest in transformations (nonidentical reproductions) that take place through inter-dimensional ‘travel,’ it is clear to see how Étant donnés is The Large Glass reproduced inside-out and back-to-front, as he claims. To see this, however, it is necessary to consider that these works are strange diagrams in different dimensional registers that are linked by the shared coordinates along their literal and metaphorical ‘seams.’

For Duchamp, the dialects of movement (how changes and stases are linked or interchangeable depending on perspective, like in mirroring)3 delivers a cerebral erotics4 that is the very basis of his entire oeuvre as well as his wider interests and activities, such as his lifelong dedication to chess. His works depict the erotics of sex and love, but, crucially, they also develop, produce, and perform less familiar erotics—diagrammatic erotics—that operate purely in thought experiments centered around theories of n-dimensional spatial movement. Such operations stay true to and highlight Duchamp’s long-term fervent eschewal of experiential aesthetics in favor of cerebral erotics, also documented in many interviews and in his own writings, but most importantly performed by his works.

Duchamp, Marcel. Chocolate Grinder #1. 1913. Oil on canvas. 24 3/8 x 25 3/8 inches. Framed: 25 1/2 × 26 5/8 × 1 5/8 inches. Accession Number: 1950-134-69. The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA. Copyright: Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp.

To begin with, in 1964, talking with Calvin Tomkins, Marcel Duchamp said:

All this talk about the fourth dimension was around 1900, and probably before that. But it came to the ears of artists around 1910. What I understood of it at that time was that the three dimensions can be only the beginning of a fourth, fifth, and sixth dimension, if you know how to get there. But when I thought about how the fourth dimension is supposed to be time, then I began to think that I’m not at all in accord with this. It’s a very convenient way of saying that time is the fourth dimension, so we have the three dimensions of space and one of time. But in one dimension, a line, there is also time. I also don’t think that Einstein in fact calls it a fourth dimension. He calls it a fourth coordinate. So my contention is that the fourth dimension is not the temporal one. Meaning that you can consider objects having four dimensions. But what sense have we got to feel it? Because with our eyes we only see two dimensions. We have three dimensions with the sense of touch. So, I thought that the only sense we have that could help us get a physical notion of a four-dimensional object would be touch again. Because to understand something in four dimensions, conceptually speaking, would amount to seeing around an object without having to move: to feel around it. For example, I noticed that when I hold a knife, a small knife, I get a feeling from all sides at once. And this is as close as it can be to a fourth-dimensional feeling. Of course from there I went on to the physical act of love, which is also a feeling all around, either as a woman or as a man. Both have fourth-dimensional feelings. This is why love has been so respected!5

Here we see two of the most significant concerns in Duchamp’s oeuvre: the adequate representation of love in aesthetic form, but without expressionist conceits; and the adequate representation of movement as a fundamental element of imagination, thinking, and erotics.

Both themes are consistent across, but not always explicit within, the huge corpus of writing on Duchamp’s work, and indeed he himself often refers to these ideas. For example, when talking with Tomkins about one of the first ‘readymades,’ Bicycle Wheel (1913), Duchamp describes that it was important because of “the movement it gave, like a fire in the chimney, moving all the time.”6 Duchamp explains how movement incorporated into his work was more important than expressing or depicting movement as such. He makes an important distinction in this regard with respect to the painting The Chocolate Grinder (1913). It is far more sophisticated in its embodiment of movement than his 1911 painting Coffee Mill, which appears more in the tradition of dada diagrammatics, with its fragmented forms, repetition of the handle in different positions as it turns in time, the arrow depicting the turning of the handle, and the dotted lines tracing that movement. The Chocolate Grinder, however, appears to be a traditional single-point perspectival representation of a three-drum grinder depicted in stark chiaroscuro, but in fact it is pregnant with the possibility of movement. The grinding drums seem ready to heave into rolling motion, as if they would fall towards the viewer on the inclined plane of the base, around the axle firmly spearing the center of the drums in place through their central point of horizontal rotation. Tomkins questions Duchamp on movement after a conversation about Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso’s analytic Cubism, in which Duchamp is scathing about what he sees as the firmly traditional character of their paintings:

Imagine, in a world like the … world of the early Cubists like the landscapes of Picasso and Braque of 1909 and ‘10, nobody had an inkling of describing movement at all. … Completely static. They were proud to be static, too. They kept showing things from different facets, but that was not movement.7

In reaction to the static quality of Cubism, which Duchamp had surpassed by 1912 with his Cubo-Futurist paintings, he says to Tomkins:

So I went on. The first thing I did in the direction of the Big Glass was The Chocolate Grinder … Well, yes, [there is movement] but not expressed. We know it should turn, but it was not trying to express the movement of that chocolate grinder at all.8

What Bicycle Wheel and The Chocolate Grinder share is that they infer movement: the grinder should turn, and the bicycle wheel can rotate on its axle, creating a spinning vertical circle, and it can turn horizontally through 360 degrees, as it can be spun on its bearing embedded into the seat of the stool. This infers that it is a machine to produce a floating sphere (the spokes of the wheel should ‘disappear’ when spinning). It is a sculptural object that produces a to-be-imagined three-dimensional sphere from an ostensibly two-dimensional circle. But, because it is not motorized—like his Roto Reliefs, which when spinning create the illusion of 3D pulsating forms or voids from 2D circular spiral designs—nor is it spun by a gallery assistant at The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, where an exact 1964 replica of the 1913 version (with straight forks) resides, or at the galleries of MoMA, New York, where a 1951 replica of a later version (with more modern curved forks) resides, we can confidently say that this otherwise static object infers movement, and that this is its function. However, it not only infers movement in two-dimensions and three-dimensions, it also infers movement from one particular dimensional register to another without actually moving itself.

More important than what Duchamp said or wrote about his works, which is notoriously opaque and/or deliberately unreliable, is that we see this fascination with the inference of both love (sometimes the erotics of imagination, sometimes the literal phenomenon of a subject loving something or someone, in either a sexual or Platonic manner) and movement (the mechanics of imagination) demonstrated in his works time and time again in the use of geometry; either literally in the use of explicit references to mathematical geometry, or in forms that function because of their actual or implied geometrical possibilities. Also, another key factor in considering Duchamp’s works is the plotting of coordinates from one work to another, mapping a collinearity that may not be immediately apparent. Such rational operations are derived from his keen interest in non-Euclidean geometry (either elliptical or hyperbolic), projective geometry, and explorations of spatial multi-dimensionality.

The writings of art historian Craig Adcock show us that Duchamp had read the work of 19th-century mathematician Espirit Pascal Jouffret, and that many of his theorems are legible in Duchamp’s pieces. Jouffret demonstrated in algebra how geometrical rotations in n+1 dimensional space could allow for the superposition of symmetrical shapes or forms, which is otherwise forbidden in their shared n dimensional register. This is best described by the example of a pair of gloves: a right-hand glove cannot fit inside a left-hand glove, because the ‘thumbs’ are on opposite sides; however, if one glove is pulled inside-out (rotating it through a 4th dimension of space) they can be superposed in 3-dimensional space (one inside the other). Such an n+1 dimensional rotation begins to explain Duchamp’s claim that The Large Glass and Étant donnés are one and the same ‘thing.’ Also, Adcock makes the point that this is also how we begin to explain that Duchamp’s alter ego Rrose Sélavy is Duchamp, but after a ‘demi tour’ through the 4th dimension—that is, Duchamp turned inside-out.

Similarly, it is known that Duchamp read the works of French mathematician Girard Desargues (1591–1661), whose work on the algebra of intersecting planes in conic sections is thought to be the foundation of projective geometry. Desargues is credited with the first documented theory that parallel lines meet at infinity (a key tenet in understanding the mappings between standard Euclidean geometry and non-Euclidean hyperbolic or elliptical geometries). Essentially, Desargues dedicated much of his work to analyzing the conic geometry of models of Renaissance perspective, exploring how the lines emanating from a center of perspective (either the human eye looking, or the vanishing point at the horizon) create cones through which planes can be intersected at various angles upon which ‘images’ are ‘projected’—the most straightforward of which is the vertical ‘picture plane’ that is the foundation of the structure of most Humanist Renaissance art. However, the extrapolations of Desargues’s work, where projection planes at different angles can be demonstrated to correspond in complex parametrical operations, led him to his most well-known theorem: “Two triangles are in perspective axially if and only if they are in perspective centrally.” This can be restated as: if the lines joining corresponding vertices of two triangles are concurrent, then the intersection of corresponding sides are collinear. This means that if the center of perspective shared by drawing straight lines through the corresponding indices of each triangle moves, or if the axis of perspective shared by all the points of intersection of all the extended vertices of each triangle moves, or both move, then the triangles are deformed proportionally according to the ratios of their axial and central collinearity. Such proportional deformations are what we see in Duchamp’s Small Glass (1918) in Tu m’ (1918), and in The Large Glass’s many different perspectival systems. This demonstrates that Duchamp was interested in the contingency of otherwise-made-constant elements of art-making, such as horizon lines, centers of perspective, plus other more complex axes of values and sign systems, which he would treat as malleable and ‘serially variable’ in a manner of complexity suggested by such theorems as Desargues’s—unlike the work of even some of the most seemingly transgressive of his Dadaist and Surrealist friends and colleagues, such as Francis Picabia.9 Also, the importance of triangles in the works of these mathematicians could also account for Duchamp’s obsession with the number 3 and its multiples.

Such rational collinear malleability of constants, or invariants, may have also been inspired by Duchamp’s knowledge of Henri Poincaré’s Science and Hypothesis (1902–5), where Poincaré’s investigations of non-Euclidian geometry and his theory of the fourth dimension refute the absolute invariant nature of geometrical theorems and postulates. In a long passage, Poincaré explains:

… [W]e do not experiment on ideal straights or circles; it can only be done on material objects. On what then could be based experiments which should serve as the foundation of geometry? … The axioms of geometry therefore are neither synthetic a priori judgements nor experimental facts. They are conventions … disguised definitions.10

Such a verbose iconoclastic attitude may have inspired Duchamp to take the same view of all of the conventions of representation in art and aesthetics, as well as, of course, phenomenal reality and the nature of conscious access to it, and most importantly of all the many spurious rules of the art academy at the time regarding how ‘the given’ is to be represented/reproduced in and through art. What is sure, however, is that the combination of projective geometry, non-Euclidean geometry, and four-dimensional geometry that Duchamp was reading during the first and second decades of the 20th century strongly impressed upon his thinking and working methods the notions of serial variance, malleability, and transformation, and the possibilities of rational mapping of such forms and processes of change no matter how removed from phenomenal experience, which all remain constant themes and operations in his works from 1913 onwards.

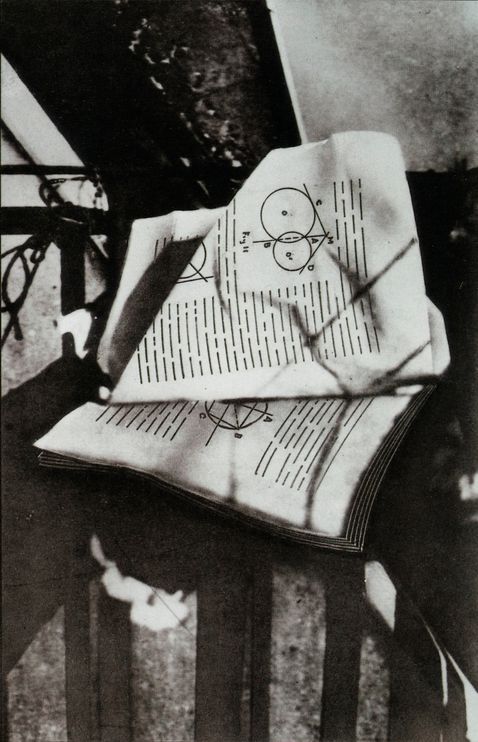

A crucial piece in this respect is Unhappy Readymade (1919) conceived of by Duchamp in Buenos Aires, Argentina (but produced by Suzanne Duchamp following instructions sent in a letter from her brother),11 which is directly related to love, geometry, and movement. This piece was a geometry book tied at one corner and hung from a balcony at the apartment of Duchamp’s sister, on Rue La Condamine in Paris, France, to be torn apart by the wind and rain (literal movement). It was also a wedding gift to Suzanne Duchamp and her husband Jean Crotti (celebrating, or perhaps berating, love).12 Here Duchamp also deliberately introduces chance—as a form of encounter and as a driver of ‘movement’ and imagination (erotics)—as a medium to have this gift of filial love, which also celebrates matrimonial and sexual love, actually act in the way that love acts, that is, by chance.

Duchamp, Marcel. Unhappy Readymade. 1919. Original destroyed. Replica re-touched photography in Le Boîte en valise de ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy / The Box in the Valise of or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy. no. VII from the deluxe edition (Series A). Collotype With Pochoir. Accession Number: 1988.1.196.30. Gift of Paula Zurcher in honor of her mother Elizabeth H. Paepcke. Achenbach Foundation. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA. Copyright: Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Estate of Marcel Duchamp, 2019.

Unhappy Readymade, by contrast to many others of Duchamp’s works, is not only not fabricated by [Marcel] Duchamp’s hands, but is also a fragile object thrown into the wild elements to take its chances and be destroyed. The two-dimensional strata of the book (i.e., its ‘flat’ pages) are folded and crumpled by the wind as it spins on its wire axis, transforming the planar pages into three-dimensional forms. We can confidently assert that all of Duchamp’s works from this period onwards necessitate the incorporation of chance, either as a medium directly, with its brutally raw operations, as in the case of Unhappy Readymade, or, as in the case of 3 Standard Stoppages (1913–14), as a powerful inference that underpins the conceptual matrix that form all his works’ functional efficacy as diagrammatic machines, which force into being abstractions as yet un-experienced or un-thought. In other words, chance is used by Duchamp to provoke the inference of the ‘not yet possible’ to begin constructing the impossible—to infer the hidden within the given: the erotics of ontogenesis.

Further exploring the diagrammatic character and function of this and other works by Duchamp, David Joselit traces a path through mathematics and philosophy that leads him to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s writings, where he focuses on their notion of “abstract machines,” to unpack Unhappy Readymade’s mechanics:

Defined diagrammatically … an abstract machine is neither an infrastructure that is determining in the last instance nor a transcendental Idea that is determining in the supreme instance. Rather, it plays a piloting role.… [It] does not function to represent, even something real, but rather constructs a real that is yet to come, a new type of reality.13

If abstract machines, such as Duchamp’s works, are neither infrastructural nor transcendental in these ways, then they can be said to also operate as love or erotics operate. Love and erotics take a subject by chance, unexpectedly. Love and erotics are not infrastructural to a given system’s formation, but nonetheless exist as a symptom or side effect, perhaps even a short-circuiting or malfunctioning of a given complex system’s operations, and can intervene at unexpected moments in its workings to disrupt the otherwise expected order or direction of its operations. Contrary to typical conceptions and characterizations of love and erotics, I argue that neither is structurally transcendental. In fact they can be described as the opposite, mundane, in useful ways. Not only have many psychologists (and poets and novelists) recorded over very long periods of time very similar typical descriptions of patients’ (or characters’) symptoms when ‘in love,’14 but we can argue from a rationalist perspective that rather than being beyond or above the range of normal or merely physical human experience, or existing apart from and not subject to the limitations of the material universe, love and erotics are a part of the normal range of physical human experience and do not exist apart from it, and are subject to the limitations of the material universe precisely because they are constructions of the human brain, which is an existent biomechanical material form, albeit a highly complex one. Love may simply be just one of many different intense concatenations of neuro-electrical storming with specific oxytocin hormonal flooding, caused by a combination of long-term mostly hermetic behavioral conditioning and the presence of certain patterns of sensorial stimuli. This triggers similar and often repetitive series of behavioral effects in the subject who has fallen in love. At base, love is merely a particular kind of ‘focus,’ albeit one that is experienced ‘all around’ and, we might say, in the infinitive. Also, the ‘piloting role’ of the abstract machine, described above, has quite obvious (if not also quite crude) sexual connotations of penetration, as the abstract machine ‘drills’ into the existent reality to twist and reconfigure it to a new reality yet to come.15

In similar ways to the operations of love, Unhappy Readymade has no possibility of determining anything, as even its own fate as a physical entity relies entirely on contingency: Would Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti make the piece? Would it be destroyed by the wind, rain, and sun? Would documentation of its performance remain? Also, its own conceptual matrix remains indeterminate, as its form, typically the carrier of conceptual coherence, is so indeterminate: Is it a physical object? Is it a performance? Is it simply an instruction? It is, of course, all of these contradictory elements; essentially, it is a concept that ‘pilots’ their possibility and simultaneously destroys their individual real actualities.

By contrast, Duchamp’s most well-known masterwork, The Large Glass (1915–23), is far more obviously diagrammatic and machinic. It is also well known to be a machine of erotics, as Duchamp often stated. We know from interviews and from his writings that it is a diagram of sexual courtship, with bachelors masturbating in the bottom half, attempting to seduce the bride in the top half. But it is only when considering The Large Glass alongside its counterpart, Étant donnés (1946–66)—which Duchamp claimed both in writing and in interviews were one single work reproduced and made manifest in different dimensional registers, serially variable—that we see the full extent to which his works are abstract machines in the Deleuzo-Guattarian sense.

Diagrammatic interpretation of the Large Glass as completed (in Arturo Schwarz ed., Marcel Duchamp: Notes and Projects for The Large Glass, London: Thames and Hudson, 1969, pp.12–13).

To do this, however, we must first examine the ways in which this single two-part work is indeed diagrammatic, and a machine of abstraction. Deleuze-Guattari scholar and artist Simon O’Sullivan gives us a primer to structure our analysis of this work:

The intention … is to think specifically about the diagram … or, again, of diagrammatics as a form of expanded aesthetic practice—as well as, more generally (following Félix Guattari), about the role of diagrams in the more ethico-aesthetic practice of the production of subjectivity.… [Diagrammatics] forms a certain abstraction (from its various sources), suggests connections and compatibilities (across different terrains), and ultimately offers a certain kind of perspective (a meta-modelization) that might be considered a speculative fiction.16

Given that it is well documented that Duchamp was interested in multi-dimensionality and projective geometry,17 we can consider that in these terms The Large Glass and Étant donnés deploy an expansive and expanding framework of aesthetic praxis (the production of art within a given art institutional complex, in the formal abstract sense) in the service of attempting to produce different forms of subjectivity—or, at least, they push so far beyond what the given collective subjectivity of the art institutional complex at the time of their making could recognize or accept as an art form that they create ruptures in the discourse of art that are still difficult to map. Clear evidence for this is that throughout his career, Duchamp’s works could never be adequately categorized, whether by artists or art historians, for whom his works escape the logics of groupings and taxonomies because of their inherent strangeness and their in-built contradictions (or at least what seem to be contradictions from the vantage point of art historical methodologies of categorization). Similarly, these works “form certain abstractions from various sources” and suggest “connections and compatibilities across different terrains,” such as the two forms of representational abstraction that make up the two halves of The Large Glass. There are also one-dimensional elements of The Large Glass: the lines where the glass is cracked, as well as the metal bands that traverse the join between top and bottom. And finally, there are zero-dimensional points in the upper half, which are holes drilled into the glass at the ‘points’ where Duchamp fired from a toy canon matchsticks dipped in paint, to represent the ejaculatory misfiring of The Bachelors at The Bride. These shots are three-dimensional actions represented in zero-dimensional form, as mere points. Equally, with Étant donnés, although when we look through the peephole of the barn door to view what is clearly a three-dimensional nude female figure in repose in a tableau vivant, with a two-dimensional woodland and waterfall scene behind, rendered by hand in paint from a photograph, our human binocular vision, which ordinarily gives us visual depth perception, is frustrated by only being able to use one eye and not being able to move, so there is no chance to verify three-dimensional depth by moving our visual sensory organ side-to-side or up-and-down. 3D is reduced to a frustrated 2D, making us ‘peepers’ the frustrated bachelors viewing the bride in a spatial realm our sense organ(s) cannot access, albeit except for the ‘shadow’ of this higher-order dimensional world that we can merely ‘see.’ Each of its manifestations—The Large Glass and Étant donnés—is a meta-model of each other, forming a reverberative set of asymptotic connections and compatibilities that can only be speculatively, or we might say metaphorically, rationalized. This is often referred to as the Surrealist poetics of Duchamp’s work, which may be true, but such terminology has the unwarranted and negative connotation that the work is somehow ambiguous or ineffable. This further comment on diagrams by O’Sullivan helps us to understand that this typical reading of Duchamp’s work as Surrealist is too limited, and instead we can propose that it is firmly realist—it is just that the world(s) it creates, like the tenets of complex topology across dimensions upon which it is founded, is(are) not phenomenally accessible to us in our three-dimensional spatial register:

A crucial aspect of this formal understanding of the diagram—to return to Lacan—is its ability (or at least claim) to communicate without meaning. Indeed, this is very much the diagram’s pragmatic character (it moves things on). In relation to this we might note that a text can operate diagrammatically, as in Lacan’s suggestion that his Écrits was not written so that it might be understood (the writings, rather, “must be placed in water, like Japanese flowers, in order to unfold”). Jean-François Lyotard also suggests that the sign might operate as a tensor in this sense—demarcating a “region in flames”—not necessarily to be interpreted, but rather, again, to set things in motion.18

Duchamp’s works in general, and The Large Glass and Étant donnés in particular, certainly do not elicit ‘meaning’ as such because they communicate by existing and functioning within and between different dimensional registers, the movement of which is only ever partially accessible at best via other abstractions, such as language or other abstractions of thought and imagination that can only ever attain any traction on their reference to Duchamp’s works as speculations.19 As O’Sullivan also states, “Here diagrammatics announces a kind of nesting of fictions within fictions to produce a certain density, even an opacity.”20 We could say the same about love, in that it too does not communicate with meaning as such, but merely ‘is’ when it exists. The concatenation of intense feelings that love elicits in humans creates a feeling of increased density of the value of existence (feeling more alive) in the one in love in respect of their own life, and an increased density of value of the one loved (i.e., one values the subject of one’s love more when in love than when not. This, of course, is inexplicable in some ways to the one in love, because the one loved has not really changed, but nonetheless is valued more densely by the one who loves them. Rather, the perceptual context has changed in the one doing the loving, in that they have fallen in love with them). The reasons for such increases in density are directly proportional to the level of difficulty in explaining these feelings (i.e., the opacity of such feelings), and so someone in love very often finds it difficult to explain because of what or why they are in love, other than that they are in love with the subject of their infatuation.

In such ways we can continue to explore how elements of this argument show that Duchamp’s work is realist, but of course in an intra-telic manner equivalent to the operations of love as described above. Love produces this exaggerated value of the subject that is loved in the perception of the one who loves, seeing something unseen from within the seen. Love creates new unexpected intentions in the one who loves towards the subject that is loved from within other already existent intentions that were different prior to the intervention of love. In all of this, love nests intentions and observations of different levels of intensity and density within and from each other, but it creates an experience of the destratification of these different levels of intensity and density as it erases any boundaries between them. Suddenly and unexpectedly, even otherwise previously inconsequential aspects of the one loved seem important when one is in love with a subject that one loves. For, example one might suddenly love the way the loved other eats, even though the one loving has seen the loved one eat before. Hence, the dizziness, elation, and confusion that many subjects who are in love describe of the feelings of being in love. It cannot be explained, apparently. This is a form of sidestepping; a transversal operation that love enacts and performs.

Duchamp, Marcel. Étant donnés (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas). 1946-66. Mixed media assemblage: (exterior) wooden door, iron nails, bricks, and stucco; (interior) bricks, velvet, wood, parchment over an armature of lead, steel, brass, synthetic putties and adhesives, aluminum sheet, welded steel-wire screen, and wood; Peg-Board, hair, oil paint, plastic, steel binder clips, plastic clothespins, twigs, leaves, glass, plywood, brass piano hinge, nails, screws, cotton, collotype prints, acrylic varnish, chalk, graphite, paper, cardboard, tape, pen ink, electric light fixtures, gas lamp (Bec Auer type), foam rubber, cork, electric motor, cookie tin, and linoleum. 7 feet 11 1/2 inches × 70 inches × 49 inches (242.6 × 177.8 × 124.5 cm). Accession Number: 1969-41-1. Gift of the Cassandra Foundation, 1969. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA. Copyright: Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp, 2019.

This nesting and sidestepping is also a constant theme and operation in Duchamp’s oeuvre, as parts and wholes interchange and boundaries between their discrete existence are erased or conjoined in folds. The Bride, The Bachelors, The Waterfall, The Illuminating Gas, The Chocolate Grinder, The Glider, The Waterwheel, The Oculist Witnesses, etc., all manifest differently in The Large Glass and Étant donnés, and these different manifestations of the same components existing in both parts of this single two-part, multi-dimensional work demonstrate the symbiotic meta-model status that each of the works has in respect of the other.21 These components take different forms—two-dimensional, three-dimensional, one-dimensional, or zero-dimensional—sometimes the same sometimes different, depending on which is being viewed, The Large Glass or Étant donnés. Also, many of the components exist in other works made prior to or during the production of these.22 In this way, Duchamp’s works create this nested set of interchanging parts and wholes, one component never being precisely a part nor a whole at any given time; always contingent upon the others for framework and status, which shift in their formal coherence, but always along a plane of collinearity, where they can be transformed parametrically, albeit that this plane is sometimes abstractly metaphoric and at other times experientially literal, or both simultaneously. O’Sullivan notes another related attribute of diagrams, in that they “[bring] together different models, even placing one model ‘inside’ another … [T]he diagram is a way of re-positioning existing frameworks, and of working out possible relations as well as divergences.”23

All of this is strongly reminiscent of what Deleuze develops in The Fold (1988), his famous exploration of Gottfried Leibniz’s Monadology (1720) and calculus via the theme of the baroque. Certainly, all the works of Duchamp’s oeuvre can be considered as points of inflection, or folds, in a plane of consistency where they are connected, manipulated, deformed, and transformed, but ultimately intimately integrated along various shared parameters or algorithms—sometimes literal, sometimes metaphorical, sometimes both. And equally, the erotic thrill of the concept of infinity, central to Deleuze’s reading of Leibniz, is key to Duchamp’s works; literally referred to in the title of The White Box, À l’infinitif (1966), another compendium of notes about his works.

Where Deleuze explains the importance of infinity in the thinking of Leibniz, in respect of the operations of monads and their intra-telic inevitability, we see echoes of the intertwined complexity of all the elements of Duchamp’s oeuvre:

A flexible or an elastic body still has cohering parts that form a fold, such that they are not separated into parts of parts but are rather divided to infinity in smaller and smaller folds that always retain a certain cohesion.24

Echoing this, we can say that Duchamp replaces more typical conceptions of ‘representation’ or ‘reproduction’ (where one entity creates another discrete entity), in his work from 1912 onwards, with transformation, deformation, malleability, folding, enfolding, and unfolding—a revealing of hidden possibilities of the affordances or tolerances of the plane of consistency within which he is working. Reproduction in Duchamp’s works is treated as a manipulation, deformation, or transformation through space and time, where what is reproduced is still intimately connected to its progenitor; a new point of inflection in a dynamic undulating, folding, and unfolding total system. It is a concatenation of simultaneities, an erotic experimentation that reveals itself ‘all around’—like the multi-dimensional performativity of a basic verb form, ‘the infinitive’; without a particular inflection binding it to a particular subject or tense, encompassing, enveloping, enfolding, and unfolding simultaneously, happening in the past, the present, and the future—like the feelings of being in love—but never severing it to become discrete and thus functionally idealist.

The contention here is that Duchamp’s entire oeuvre is dedicated to a materialist exploration of dynamic contingent forces, and that it eschews more typical idealist preconceptions of abstractions (especially found in attitudes to art-making), such as is often found in the typical ways people conceive of the most abstract of phenomena, ‘love.’ There are striking similarities with the materialism of Deleuze and Guattari’s Mille Plateaux (1980) that further help articulate some of the mechanics of Duchamp’s project in this regard. For example, as philosopher and Deleuze scholar Ray Brassier explains:

The materialism laid claim to in A Thousand Plateaus is unlike any (other).… It does not pretend to accurately represent an objectively existing ‘material reality’ (whether natural or social), just as it does not propose practical imperatives derived from universal laws (whether natural or social). It seeks to conjugate an ‘abstract matter,’ conceived independently of representational form, with a concrete ethics, wherein action is selected independently of universal law.25

Brassier goes on to say, “Here the abstract is no longer the province of the universal (invariance, form, unity) and the concrete is no longer the realm of the particular (the variable, the material, the many). The abstract is enveloped in the concrete such that practice is the condition of its development.”26 So, here, if Duchamp’s primary subjects are love and movement—perhaps, as we have seen, synonyms in the world of Duchamp’s oeuvre—we can assert that these are an abstract matter always independent of representational form as such. The introduction of an absolutely contingent ground that we find in Duchamp’s claims to multi-dimensionality, always at play in his work, and the interchangeability of parts and wholes, prevents the possibility of any universal law governing action per se in a particular reality either represented or experienced (or indeed, in one only experienced in the imagination), as the always already possible (theoretically at least) piercing of any given order of reality (or dimensionality) by another order of reality (or dimensionality), and the concomitant transformations that such piercings produce, are ever-present, as demonstrated in the diagrammatics of his works. Thus, Duchamp’s work does not propose any practical imperatives derived from universal laws. Instead, what nominal laws or rules may exist or be represented in Duchamp’s works operate transversally, cutting across and through various other given rules, conventions, formats, forms, and systems (especially systems/regimes of representation) much in the manner that love rampages transversally through the given value-system(s) of a person struck by it, re-orientating, rotating, and generally disrupting and transforming their world, both literally and metaphorically.

The question of what kind of disruption of rules are created by such abstract machines as love or Duchamp’s work can be well explained by the following passage from Brassier, where he describes the consequences of thinking through Deleuze and Guattari’s re-conception of the relationship of the abstract and concrete:

Rules are no longer abstract invariants that need to be applied to concrete or variable circumstances. ‘Abstract’ now means unformed and ultimately, as we shall see, destratified … [A]bstract matter is described as constituting a ‘plane of consistency’ characterised by ‘continuums of intensities’, ‘particles-signs’ and ‘deterritorialized flows’.… [They] insist that this plane of consistency (which they also call ‘multiplicity’) must be made, since it is not given: … made by mapping what is unrepresented in both thinking and doing.27

This mapping of what is unrepresented in both thinking and doing is an excellent description of the intra-telic operations of Duchamp’s works. The destratification of the presumed coherence required of a perspectival picture plane, for example, as disrupted in such works as The Large Glass, where ‘flatness’ and ‘illusionistic depth’ sit side-by-side in one work without hierarchy. We see this precisely in Duchamp’s final painting Tu m’ (1918), perhaps the first of his three great masterpieces, where we find a seemingly random array of pictorial conceits, apparently jumbled together in the long slender canvas. Incongruous and divergent perspectival systems reside on either side of the painting, elongated painted shadows of readymades hover in the middle distance, a perfectly flat sign-painted pointing hand guides us from left to right, the canvas is slashed and held together with safety pins in the center, and a bottle-brush sticks out at ninety degrees to the canvas surface. As confusing as it may seem, with all of these divergent picture-making methods clashed together, it is made coherent if we consider that this painting is a manifesto for giving up painting—for giving up a representational art based on abstract invariance that is typically applied to concrete or variable subject matter. The function of Tu m’ could be said to de-stratify the entire tradition of Western art, and to institute an art that is a ‘plane of consistency’ that operates via ‘continuums of intensities,’ ‘particles-signs,’ and ‘deterritorialized flows’ that allow art forms to flow between different dimensional registers—between the realms of thought and matter as material abstractions in each realm, taking different forms depending on context, but preserving collinearity throughout.

Duchamp, Marcel. Tu m’. 1918. Oil on canvas, with bottlebrush, safety pins, and bolt. 27 1/2 x 119 5/16 inches. Accession Number: 1953.6.4. Gift of the Estate of Katherine S. Dreier. Yale university Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut. Copyright: Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Estate of Marcel Duchamp, 2019.

This materialist character of Duchamp’s work is what lends it its pragmatic functionality also. The provisional, revisable quality of ‘the diagrammatic,’ of ‘abstract machines,’ and of ‘the baroque’—this anti-idealist pragmatism—is observed also in the “definitively unfinished” status of The Large Glass. From the many preparatory drawings in The Green Box it is possible to show that several planned elements are left out, such as The Boxing Match, The Butterfly Pump, The Toboggan, and others.28 Also, Duchamp referred to Étant donnés as an “approximation démontable”29—the phrase which greets the reader of his 1966 Manual of Instructions for the assembly of Étant donnés.30 Throughout the instructions he gives much latitude for a would-be disassembler/assembler of the piece to make their own judgements about the precise placing of some of the elements (d’Harnoncourt, Introduction to the Manual). This confirms the pragmatic attitude that Duchamp had towards art in general, and that his works embody and perform specifically. It also attests to their strategic conceptual robustness, in that they do not even need to be made or reproduced absolutely perfectly or ‘finished’ to function perfectly. This is a far cry from what may seem like the petty/petit Humanism of Picasso and Braque’s Cubism, where not only the hand of the artist is so necessary and important, but also the absolute finitude of any given painting itself. This gives us a clear understanding of the depth of the rift that Duchamp made between a constantly Humanism-dominated art world ethos that surrounded him and his work throughout his life, and from which he quietly but violently extracts himself and his work.

Similarities here again can be seen with the perspectivist realist materialism of Deleuze & Guattari, as Brassier explains:

For ‘machinic pragmatics’, the efficacy of performance can no longer be subordinated to pre-established standards of competence. So long as practice is subordinated to representation, it can only more or less adequately trace a pre-existing reality, according to extant criteria of success or failure. But machinic pragmatics is not geared towards representation; it is an experimental practice oriented towards bringing something new into existence; something that does not pre-exist its process of production. It de-couples performance from competence. It does not engage in utilitarian tracing of the real; it generates a constructive mapping (and as we shall see, a diagramming) of the real….”31

The manner in which Duchamp’s entire oeuvre was constructed and developed operates in this mode of performative praxis, where abstractions are combined and re-combined in radically surprising, unfamiliar, and sometimes frustratingly opaque ways. This radical opacity of the works stems not, as is often claimed, from the shocked reactions to his work,32 but rather it is Duchamp’s constant tracing of what is not yet accessible to consciousness in relation to what cannot be ‘felt’ in the tactile three-dimensional world or ‘seen’ in either the spatial three-dimensional world or the planar two-dimensional world, which humans typically have phenomenal access to, that creates this density, opacity and dynamism.33 His interest in the fourth-dimension of space, and other dimensional registers is fundamental to understanding this, and is what generates the radical machinic abstract quality of his work.

In conclusion then, I am arguing that Duchamp’s entire oeuvre from 1912 onwards is both a diagrammatic form of love and life, not only because it putatively depicts love, love-making, and erotics, which are important here, but also and more importantly because as diagrammatic forms, as abstract machines, the way the elements depict what they depict actually operates in ways identical to the way that love and erotics operate. My argument here is that love is a feeling that is a diagrammatics of itself as life. As Duchamp’s alter ego’s name suggests, Rrose Sélavy (“Eros, c’est la vie” = “Love is life”), life and love are intra-telicly identical and without one the other does not exist: life without love is merely survival, and love cannot exist without living subjects that are truly living. Duchamp’s diagrammatics brings into existence maps towards the possibility of forms of love that may not be accessible to us (yet), but which nonetheless have been mapped in forms that we can access, in anticipation of the future evolution of our capacity to think and feel in ways that will extend what it currently means to love.