Initially conceived as an uninvited exhibition focusing on homosexuality and cruising cultures at the 2018 Venice Biennale of Architecture, the Cruising Pavilion has since mutated into a curatorial project, which, after a second show held in New York last winter, is preparing a third one this fall in Stockholm, at the National Museum Architecture of Sweden (This interview took place before this third show opened). While each of these shows is entirely different, they all pursue the same goal: exploring the many ways in which cruising practices have challenged and continue to challenge architecture—whether urban planning, established architectural discourses, or the conception of public spaces. Beyond its subversive origins in the Venetian context, the growing institutionalization of this project underlines the importance of a question that, in fact, has been raised from the outset: how to deal with the contradiction of wanting to expose practices that, most of the time, have emerged and continue to develop against and despite a public view from which they are trying to escape. In other words, how to exhibit subversion? The following conversation discusses the parallel and sometimes contradictory lines between the way cruising cultures are meant and seen to be challenging architecture, and the ways in which darkrooms and white cubes can be read as opposite spatial types.

Glass Bead: First things first: What is the Cruising Pavilion?

Rasmus Myrup: The Cruising Pavilion is a curatorial project focusing on gay sex, architecture, and cruising cultures. It is led by four friends: artist Rasmus Myrup, architect Octave Perrault, and the curator duo Charles Teyssou & Pierre-Alexandre Mateos. We are all based in Paris.

The group came together around the first exhibition we organized at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2018. The Cruising Pavilion was initially the name of this exhibition, which showed the works of over 20 artists and architects inside the warehouse-like project space Spazio Punch on Giudecca. The richness of the topic and the positive response we received convinced us to transform the project into an exhibition trilogy, with each edition taking place in a different city with different works. The second edition took place this winter 2019 in New York City at Ludlow38, the Goethe Institute gallery, after an invitation by curator Franziska Wildförster. The third and last one will open in September 2019 at Arkdes, the Sweden’s National Centre for Architecture and Design, located in Stockholm, after an invitation by curator James Taylor-Foster. Besides the exhibitions, we also have participated in various talks and events along the way and are thinking of gathering everything into a publication after the show in Sweden.

GB: In Venice, the Cruising Pavilion aimed to break into the famous biennale, notably challenging the notion of ‘freespace,’ chosen as the main theme of the entire exhibition that particular year. Used in the curators’ manifesto as the cornerstone of architecture’s putative tension towards indeterminacy, the notion of ‘freespace’ seemed to foreground a deeply liberal account of freedom, conceiving it in essentially negative terms (that is, freedom conceived as the liberation from constraints).1 In an ironic twist that largely informed your curatorial intervention, you proposed what you called “urgent revisions” to this manifesto, simply replacing freespace by the term cruising. Beyond the joke and the critique that consisted in underlining how meaningless these utterances about freespace could appear, it seems that your revised version of this manifesto also called for a more positive understanding of freedom, more profoundly articulated to its objective conditions of possibility and, thus, to a questioning of freedom as empowerment. How much was the Cruising Pavilion a response to this particular biennale? How much was cruising used as a weapon against this liberal notion of freespace?

Octave Perrault: The Cruising Pavilion was not part of the official Biennale. And as a completely independent pavilion, it had to actively subvert the biennale and its culture. Considering the spirit and the subject of the show, it was also an integral part of the curatorial approach. Indeed, we had been thinking about doing projects on architecture, sex, and cruising in different ways over the few months before the biennale. The biennale provided a strong context for formalizing a show on the subject with a clear location, a date, a format (that is, a pavilion), and an established architectural culture to react to.

To answer your question, this first exhibition was more of a response to biennales in general and the architectural discourse at large rather than this specific one. The editing of the manifesto was one of the elements illustrating this. A couple of months before the opening, there was basically no information out apart from a few press statements by the curators and this weird freespace manifesto. I was told that the silence was a conscious choice made by the curators to somehow build expectations, which was also followed by the national pavilions who hardly communicated anything about their own shows. What a distorted marketing strategy! Strategy that to me, can be seen as a symptom of the weakness of today’s architectural discourse. We are at a moment when architecture has lost its esteem because it is divorced from many contemporary debates. One of the greater challenges is to rebuild the legitimacy of its discourse in culture at large. And for that, we need to take clear and relevant architectural positions that can garner support.

Actually, the “Cruising freespace manifesto” might be more about contemporary architectural curation than a reflection on freedom. Freedom, liberty, liberalism, free market, light and space, generosity… What were the curators trying to say? The biennale’s manifesto used the most general pseudo-poetic terms without much of a stance or question. There was little to agree or disagree with. Our edit simply said that it could be otherwise. If every architecture biennale was about one specific topic, clearly developed and problematized, a solid discourse could progressively emerge. I could imagine such a methodology working well with architects who are used to responding to a brief. Such a methodology could also establish a curatorial culture specific to architecture, which demarcates itself from its artistic model.

That being said, I would agree about freedom as empowerment instead of freedom as liberation from constraint. It is about a form of resistance that works within and against rather than about a search for an outside. This is very much aligned with contemporary theories of emancipation that have developed since post-structuralism, I would say. In fact, architecture is perhaps the only cultural domain where freeing from constraints remains a dominant lexicon of action. Most architectural projects are still justified through the breaking or softening of walls, structures, orthogonality, materiality, order, etc.

Henrik Olesen, Pre-Post Speaking Backwards, 2006. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin, Cologne, New York. Installation view of Cruising Pavilion, Venice. Image by Louis De Belle, 2018.

GB: Far from any romanticization of cruising, you framed your reflection in relation to contemporary transformations that deeply affect its practice and experience: “Geosocial apps [you argued] have generated a new psychosexual geography spreading across a vast architectonic of digitally interconnected bedrooms, thus disrupting the intersectional idealism that was at play in former versions of cruising. Today, class, race and gender might be as regulated by the erotic surface of the screen as the architecture of the city.” To what extent was your critique of ‘freespace’ articulated to one that could be launched against cruising in a context in which its practice seems increasingly neutralized and commodified by platforms that sometimes share more with Facebook than with the more subversive origins of cruising practices?

OP: Part of our position––at least mine––is to precisely refrain from such polarized frames of thoughts. The power of subversion that ‘original’ cruising enjoyed is real but it is also romanticized because it was also arguably more dangerous and criminalized back then. The neutralization and commodification of sexualities through apps is very real too, but that does not completely hollow their political potency; plus, there is the fact that they are now present and unlikely to be going away anytime soon. It is best to understand them and cultivate a critical engagement with them.

I truly hope that our exhibitions are explicit in this regard. We are not mourning a lost past nor simply embracing the present, but working with the tension between the two. Cruising is highly specific and everyone seems to have a different definition for it. We are conscious that we are talking about cruising in a limited manner, through a heavily European and North American lens, but we are actively working on balancing the positions with a variety of works that do not provide a uniform definition of cruising nor a complete history of it.

Your question about whether apps for sex are freespaces when they are at the same time very controlled, comes down to asking whether we can even speak of an architecture of cruising. The image of cruising as a resistance to normative totality does not really lend itself to architecture, which is the art of ordering things in space, and thus by definition very un-queer. Looking for an architecture of cruising is already a polemical question. Tom Burr’s and Henrik Olesen’s texts on cruising might be the ones most directly speaking about cruising as both a free and dangerous practice in reappropriated spaces. Andreas Angelidakis’s DIY gloryhole labyrinth manual shows cruising as a playful game. The bathhouse by Studio Karhard shows that cruising has also been subject to a form of institutionalization with the creation of dedicated designed spaces that interestingly turn the aesthetic of a ‘wild’ form of cruising into a design language. And Andres Jaque’s videos are at once about the ways dating apps are used by governments to target gay men in certain areas of the world and about the way dating apps are the medium through which gay refugees have managed to accelerate the reconstruction of their lives.

Studio Karhard, Boiler Club Extension, 2015. Photos by Stefan Wolf Lucks, courtesy of the architects. Installation view of Cruising Pavilion, Venice. Image by Augusto Maurandi, 2018.

One of the curatorial challenges of the upcoming show at ArkDes in Stockholm, the National Architecture Museum of Sweden, is to maintain and convey the complexity of these perspectives. The exhibition needs to be strongly stating what cruising is because it will be very alien to a large majority of the audience–kids and families–but it also needs to highlight the complexity and nuances that the topic deserves. What will be radical to many of them will be common sense to others. The ambiguity you point out with regard to digital technologies also concerns our curation in general: Is it right to expose cruising this much? Are we helping or are we complicit? Are we capitalizing on it? Can and should we define cruising, even? We ask ourselves these questions all the time and they are a driving force behind the project. The approach we always follow is that it must be done well and to the right extent.

This issue has been particularly vivid with regards to non-men cruising practices and their architecture. The very premise of this question is debatable. There is much less known material, and we are personally not in a position to say much, and yet, at this point, it has become one of the most interesting and lively frontiers in the project. People have been engaging with it more than any other points raised by the exhibitions, both intellectually and by actively trying to set up real spaces. For example, the parties that Maud Escudié is now organizing were partly triggered by the conversations around the project, including one between her and Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings during a talk Pierre-Alexandre and Charles did at FIAC. This is why we showed her party flier in the New York exhibition. The works related to gay male spaces and practices were more about re-reading certain histories or revealing them. They provided extremely valuable context but generally did not have the same urgency as certain works that expand the edges of what cruising might be, such as Shu Lea Cheang’s film for example. Overall, if the Cruising Pavilion participates in furthering the subversiveness of cruising beyond its traditional definition, we are doing a defendable job, I believe.

Shu Lea Cheang, I.K.U, I-robosex, 2001. Film. Courtesy of the artist. Installation view of Cruising Pavilion, New York. Image by Jason Loebs, 2019.

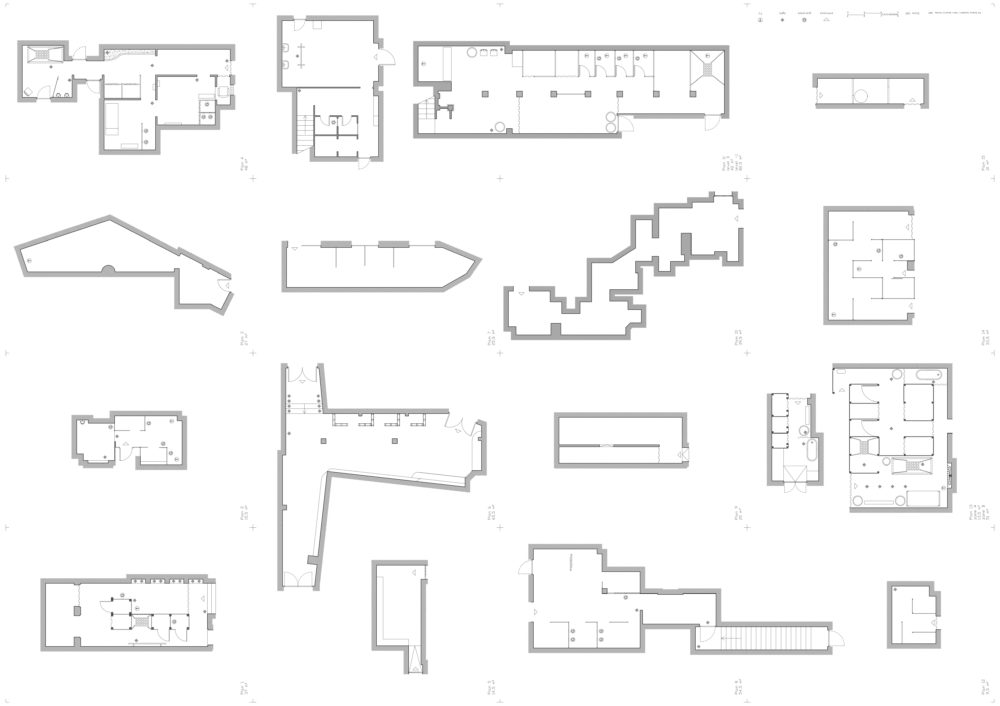

GB: When presenting the first Cruising Pavilion, in Venice, you notably stated that: “Somewhere between anti-architecture and vernacular, the spatial and aesthetic logic of cruising is inseparable from the one of the proper metropolis. Cruising is the illegitimate child of hygienist morality.” This conception stems from a historical reading of cruising as a practice that, in response to the forced marginalization of homosexuality by the architecture of bourgeois domestic spaces, developed in the interstices of cities whose modernization also tended to increase their overall legibility, transparency, and discipline (as notably emphasized by Michel Foucault in Security, Territory, Population).2 Emphasizing the many ways in which cruising resisted this modernization, you also underlined how it culminated in the baroque figure of the labyrinth. Yet, in your exhibition, you showed the work of Pol Esteve and Marc Navarro, whose drawings of Barcelona darkroom plans rather emphasize how much these spaces are often the product of an extremely clear logic of partition. These plans seem to share almost nothing with the common figure of the labyrinth. Do you see this architecture as simply registering a profound transformation of the sexual practices historically associated with cruising? Or do you see in it the potential, against the established architectural discourse, to ground a non-obvious yet resolute emancipatory architecture of sexual desire? In other words, to what extent do you think we can see these plans as an alternative proposition, beyond the idea that cruising would be somehow restricted to the subversion of an existing moral and normative order?

Pol Esteve & Marc Navarro, Atlas of Plans: Barcelona Dark Rooms, 2007. Digital print, 841mm x 1189mm, Unlimited edition. Courtesy of the architects.

OP: Our reading of the figure of the labyrinth in the darkroom plans and cruising plans at large is anchored in a political history of the city which, I guess, would indeed be Foucauldian. I do not know if the labyrinth is baroque, but I can definitely assure that, architecturally speaking, labyrinths are not common. On the contrary. The greater majority of the cities we inhabit have mostly been built after the 18th century through large scale architecture projects mixing social reform and real estate developments. These were marked by a search for order in all its forms—whether moral, social, economic, or political—and spatial order was one very important means of achieving that. This is particularly visible in the reforms of the London slums in the middle of the 19th century and the reform of hotels in pre-war New York City; the smart city reforms that are now taking place across the world abide by it too, according to the dominance of efficiency and organization in its lexicon (even chaos is about organization now, in that context).

The labyrinthine quality of architectural spaces has been one of the main targets of such architectural reforms, especially at first in the domestic sphere. Disorderly rooms and plans were said to be breeding misconduct, because they resisted surveillance and also enabled unholy interactions between inhabitants. These spaces were neither living nor working quarters, neither bedrooms nor bathrooms, neither public nor private. Women, men, children, siblings, elderlies, animals, everyone was constantly interacting, with little intimacy, sharing beds and baths, and had little control over their privacy, and little awareness and value for the proper (bourgeois) private etiquette. Sex was much less of a private affair than a public one for everybody, husbands and wives included, because there was no intimacy at home. Also, homosexuality was not criminalized in the same way, and marriage was more about lineage than romance. Alongside labyrinthine architecture, the other architectural demons that had to be solved by moralist reforms were darkness and fluids, both bodily and urban. City health and body health have often been interchangeable analogies.

Shu Lea Cheang, I.K.U, I-robosex, 2001. Film. Courtesy of the artist. Screengrab by Cruising Pavilion.

What is extremely interesting architecturally is that visibility, orientation, and fluids are precisely at the core of cruising architecture. Toilets and bathhouses are dedicated spaces for bodily urban fluid management, parks are naturally labyrinthine spaces that are hard to surveil and often most active at night, and darkrooms deploy all of these attributes through architecture and design, even by subverting the codes of modernist machinic morality into a fetish. Darkness, corners, nooks, passages, wet surfaces, lubed devices: all of them are using the aesthetic tropes and logic of the modernist city, but precisely to facilitate activities that have been designed out of the city. The plans of Barcelona darkrooms drawn by Pol Esteve and Marc Navarro in 2007 are probably the best work illustrating this argument.

So, if the cruising labyrinths are surely made of partitions and materialities that belong to the modernist architectural lexicon, they articulate them in a way that is not furthering the dominant biopolitical project in that sense. And to me, one of the most important points in this regard is that the ubiquitous motif of the dark labyrinth in male cruising seems to have crystalized through practice rather than theory, like a sort of common-sense strategy of resistance, which is why we introduced the idea of a cruising vernacular and that we make exhibitions where you get lost, cannot see the artworks, and have to somewhat engage with them non-discursively. At least we try to point at that.

GB: You have stated numerous times that one of your driving hypotheses about the architecture of cruising is that it shares a lot of similarities with the architecture of exhibitions. In fact, it can be said of both that they consist of intense ‘biopolitical’ sites: be it by regulating the phenomenological access of spectators to artefacts, or by maximizing the regime of encounter between bodies and desires, they both act as spatial frames and physical stages for the political construction of subject-object relations and are, as such, directly bound to power and the fabric of its social order, whether by instituting or subverting it. You have notably framed your project in analogy with the way in which the abstract modern topos of the garden was appropriated in a seminal exhibition like Theatergarden Bestiarium,3 by concretely translating the “art of space” ushered by the architecture of cruising into the architecture of your exhibitions. While Theatergarden Bestiarium aimed to detect the emergence of the figure of the modern spectator in the baroque culture of 17th-century Europe by grounding its political formation in the development of the theater stage and the architecture of baroque gardens, the Cruising Pavilion seemed to look for producing a certain subject by exhibiting the emancipatory uses bodies can make of the specific architecture of darkrooms. How does your project make use of the codes and norms ingrained in the architecture of exhibition to bring forth such subversive, counter-hegemonic uses, without merely aestheticizing them?

Pierre-Alexandre Mateos & Charles Teyssou: Conversely to what you may suggest, the aestheticization of architectural codes attached to the darkrooms might be the most subversive act of the exhibition. To explain this point, we should briefly detail the cultural construction of manliness as an architectural fetish by darkrooms. By performing a hyperbolic version of masculinity through the use of rough concrete, bricks, wires, military pattern, and so on, these spaces render such features into drag king ornamentation. When you go to The Eagle (New York), Le Bunker (Paris), or Ficken 3000 (Berlin), it is very clear that the translation of masculinity in architectural terms is operated through the idea of opulence, décors, and postures. As such, darkrooms might be the best spatial device in order to approach architecture as a biopolitical theater in which sexuality and gender is rendered as a pure drag king performance. In the essay “Curtain Wars,”4 Joel Sanders speaks in detail about the cultural conflict between the architect and the interior designer, the two extremities of the axis that separate manliness and womanliness, authenticity and superficiality, exteriority and interiority. This dialectic found its apex with modernist architecture and alpha figures such as Le Corbusier or Mies Van Der Rohe. We believe that the design of darkrooms deeply repudiates this binary by pushing such architecture to a point of critical campiness. One of the first editions of Cruising Pavilion was to foreground such thinking by indeed aestheticizing the codes and norms of darkrooms. That said, the connection we made with the exhibition Theatergarden Bestiarium was a way to investigate the genesis of cruising and public sex practices in relation to modern spectacle. Garden, theater, and cinema have been historical sites of cruising. We could think of the labyrinth in the garden of Versailles Castle as a model for sex clubs. Theatergarden Bestiarium also focused on modern spectacle as a technology of production of subjectivity. In that line of thought, darkrooms and spaces created by dissident sexualities have embodied a counter-hegemonic force to collective sites of subjectivation such as mainstream media and social institutions. Indeed, if we follow William Burroughs’s or J.G. Ballard’s thoughts that drugs and the new media landscape have been the structuring forces of contemporary subjectivity since the fifties, one could say that some sex-clubs have been intense laboratories for the production of dissident biopolitical fiction. They enabled the invention of new ways of desiring, loving, and living that did not obey the hetero-patriarchal model of reproduction by the use of chemicals, porn, and sexual paraphernalia. Ideally, Cruising Pavilion wished to bring such sexual subcultures and their revolutionary potentials to the foreground.

OP: With regards to the architecture of cruising versus exhibition design, we have noticed that the only spaces sharing similarities with cruising spaces are exhibitions. This comparison does not apply in terms of scale, but there is a clear parallel in terms of their spatial articulation, especially with designs for exhibitions such as Les Immatériaux by Jean-François Lyotard at the Pompidou Centre5 or the more recent design for the Stedelijk’s permanent collection by OMA. Less than a real historical argument, I see this analogy to be particularly useful because both are playing with circulation, interaction, visibility, exhibition, discourse, desire, etc. There is a shared lexicon that I like to read in analogy between spatial layouts, but there is also a strong opposition in terms of brightness. The white cube contrasts with the darkroom. The discourse of the institution relies on light when that of counter-discourse needs darkness, which can also be called non-verbal and perhaps non-visual. I am not yet sure if this can be a point to develop beyond a mere observation, but it has nonetheless been a very useful operative idea for our exhibition designs, especially with regard to our shows ‘exposing’ and ‘casting light’ on cruising—that is, institutionalizing it. In short, we make exhibitions that you cannot see on purpose.

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Gaby, 2018. Digital video, 7:55. Courtesy of the artists and Arcadia Missa. Screengrab by Cruising Pavilion.

GB: While cruising was never explicitly and publicly mentioned in relation to built projects, your exhibitions display built projects in which some form of thinking about cruising practices was involved. Such an act seems to point to a contradiction that attempts at exhibiting sub-cultural or subversive practices are obligated to confront: namely, the problem residing in the fact that making public movements or practices whose subversive nature is also bound to remaining hidden from the power structures they subvert can also give traction to the way in which these structures can repress or normalize them. In the particular case of your exhibition, we could first identify this tension between the darkroom, which mainly operates despite the public gaze, and the white cube, which, understood as a generic regime of exhibition, functions on the contrary by virtue of this public gaze. If one could say in experiencing your exhibitions that it everts the museological politics of visibility, it also seems to do so by paying the price of entering this regime. Could you tell us how you theoretically and practically navigate this contradiction?

PAM & CT: The history of cruising is embedded within the persecution of homosexuals. In certain geography and for a majority of people, cruising is not a choice but the only way they can live their sexuality. For others, clandestinely, anonymity, and secrecy has become a sexual trigger. Guy Hocquenghem rightly emphasized the localization of homosexual phantasms in the very imagery of its persecution: “Why toilets, insalubrity and darkness constitute the framework of gay desire? Why those who have decided to come out of hiding continue to project their excitement in the miserable places that the system condescends to allow them and where the police provoke them?”[6] By pointing to this, we wish to emphasize the complexity of desire and its resistance to unequivocal understating in relation to power structure. Moreover, the subversive aspect of cruising does not evaporate when lighted by an exhibition, just as its counter-hegemonic power is not automatically communicated to every person cruising. In certain countries such as the Netherlands, you have parks reserved for cruisers with a rainbow signalization encircling these sexual zones. The effect of such institutionalization is ambivalent as it accepts as well as monitors a practice at the same time. With regard to the question of the dark cube versus the white cube, we wanted to highlight series of art practices that had interrogated the possibility of curating radical sexualities. Several questions surfaced in our mind during the inception of the project: How can dissident desire be expressed without being institutionalized? How can dissident sexualities retain their power and their capacity for transgression without being commodified? Our conclusion was that they do not belong to art institutions or museums. The social order that has founded these institutions as well as the very museification process opposes the idea of exhibiting sexual countercultures. Yet some of the artists featured in the shows—such as Lili Reynaud Dewar, Tom Burr, Henrik Olesen, or Monica Bonvincini—have articulated their practices around this very contradiction. Their work either shed light on a sexual history of art written in the shadow of the master figures or questioned the libidinal functioning of the museum.

Ann Krsul, Amy Cappellazzo, Alexis Roworth & Sarah Drake. “Lesbian Xanadu”, Out magazine, 1992. Magazine and print. Courtesy of the artists. Installation view of Cruising Pavilion, New York. Image by Jason Loebs, 2019.

GB: In the research leading up to the selection of artistic contributions for the Venetian version of your project, you said that you were notably interested in the connection between Minimal art, BDSM, and architecture, arguing that “masculinity, theatricality and the emphasis of non-verbal language are notions shared between these two fields.” It can indeed be said of Minimalism that it retrospectively made explicit a constitutive aspect of the modern experience of art in general, that is, the double and reciprocally referential presence of the aesthetic object as thing and sign, its “stage presence.” Seen in this way, Minimalism is also the art that most intensely foregrounded this presence in strongly anthropomorphic terms, stressing the bodily conditions under which an aesthetic event can be said to take place. How much does the connection you draw between Minimal art, BDSM, and architecture point towards such an emphasis on the embodiment of the exposure to artworks, or what we may call an erotics of aesthetic experience?

PAM & CT: Unfortunately, the budget limitations we had to work with in the different iterations of the Cruising Pavilion did not allow us to develop this connection on an experiential level. Moreover, the idea to delve into a general discourse that would take on Michael Fried’s essay “Art and Objecthood”7 in which he criticized the “theatricality” of Minimalist art in order to develop an erotic of the aesthetic experience was not our goal. The primary aim of the Cruising Pavilion was not to speak about art via the lens of cruising or art about cruising but about cruising culture itself through different cultural artefacts that seemed to us pivotal in understanding this counter-culture. Yet, via the research of Monica Bonvicini and Tom Burr, we wanted to draw the critical connection between the supposedly immaculate formalism of Minimalism and the BDSM culture. From Robert Morris, with his advertisement for his Castelli-Sonnabend exhibition published in the April 1974 issue of Artforum, to Ian White’s exhibition of Richard Serra’s HANDS video at the Berlin sex club Lab.oratory in 2008, the idea was to mock the alpha male authority that innervates minimalist aesthetic.

Plan of the Stuart Roeder House, Fire Island Pines, New York, 1973. Drawing on architecture paper Courtesy of the Horace Gifford Archive. Installation view of Cruising Pavilion, New York. Image by Jason Loebs, 2019.

GB: In contrast to the Venice exhibition, Cruising Pavilion, New York held recently at Ludlow 38 explored what happened to the libidinal history of club culture in NYC since the sixties. A notable precedent you excavated is the Ansonia Hotel, founded in 1968 by Steve Orlow, which you described as a “sexual power plant” comprising “a dancefloor, a cabaret lounge, sauna rooms, steam rooms, a roman swimming pool, an upscale restaurant, a hair salon, 400 individual rooms, two large orgy rooms, and an STD clinic.” The difference between what it represented and made possible when founded in 1968 and what has happened to cruising and sex in NYC since then grounds your call for the need, following Paul B. Preciado’s words, to “perform increasingly intricate gender cut-ups, build sexual constructivist montages and appropriate body normative dating apps to create new forms of queer situationist derives.”8 How would you situate your role as curators in relation to this call? How would you describe the role that exhibitions like yours can play in reinvigorating this culture, involving, in your own words, the notion that “cruising is not obsolete and that public sex remains a laboratory for political futures and spaces”?

PAM & CT: Firstly, we have to say that cruising does not need us in order to be reinvigorated. It is massively practiced and its contemporary mutations do not kill its original ethos even though they modify it. Concerning the role of curator in regard to the call for hacking gender, technologies, and urbanism, we think that the exhibition space should be a site for the flourishing of radical alterities, a space of physical and cognitive rush. Pierre and I are, for example, very attracted by the experiments of the early 20th century. The Constructivist theater of the early 1920s by Vsevolod Meyerhold and Alexander Tairov, for example, has been the crucible of the modern spectacle developed later by animation parks or the Hollywood cinema industry. The Pavilions of El Lissitzky, the Roxy’s production for New York’s Radio City Hall, or Herbert Bayer’s designs for exhibitions, such as Road to Victory,9 are a few examples of collaborations between the pioneers of metropolitan entertainment and avant-garde which led to the development of phantasmagorias that embraced technological curiosities, performances, and exhibition design—sometimes all together. Ideally, we think that an exhibition should provoke an altered state of mind and assume responsibility for both pleasure and knowledge, dream and horror.

OP: I feel very aligned with Preciado’s quote even though in practice I have a rather straight sex life. Also, I think that there are great lessons to learn from the histories and the strategies that led to ‘subaltern’ architectures. Architecture has been seized by dominant normative forces, but it can precisely be deployed against it for that reason. The few ‘sexual power plants’ we talk about are probably some of the best examples. I see the Continental Baths as providing a relevant variation of Rem Koolhaas’ Downtown Athletic Club.10 This work on cruising is an attempt to advance the greater urgent contemporary questions regarding gender in architecture, especially in terms of forms and design. If all the architecture we know structures genders in a way that must be undone, what do we design? Public/private; light/dark; inside/outside—they are all subject to that gendering. So what do we target, what do we subvert, what are the references and the words that should or should not be used? The methodology of Preciado should be deployed by architects and everyone, beyond the realm of queer avant-garde, in every single decision they make.

Interview conducted for Glass Bead by Jeremy Lecomte and Vincent Normand.