To be in love is to create a religion whose god is fallible.1

–André MauroisIf a machine is expected to be infallible, it cannot also be intelligent.2

–Alan TuringAmore e ‘l cor gentil sono una cosa

(Love and a gentle heart are but one thing).3

–Dante Alighieri

The history of the concept of love is linked to physicalistic descriptions of its chemistry and biology or to a transcendental plane of ideas thus leaving it cloaked in an enigma. My attempt here is to redescribe love’s traditional enigma in terms of its ‘black box,’ namely, through examining the computability of love in reference to Alan Turing’s work on intelligent machines and its analysis in an alternative way to the anthropocentric conception of love. I will discuss Turing and P-Type (pain and pleasure) and B-Type (brain) Machines; love, computability and free will; computation and concepts of the sublime in relation to love; and black boxism and computational transcendentalism.

Computers in Love: From the Chambers of the Heart to the P-Type Machine and B-Type Machine

Computing the enigma of love invokes Turing’s own effort to crack the code of the German submarines in WWII, offering not only insight into the computational logic of the code but also a glimpse into the Lifeforms that established this bio-psychological stratum through computational algorithms, its compounded symbolic residue, so to speak.

For Dante Alighieri, love is instigated in a mechanical event which incidentally informs us that the ‘brain’ is the most animal-bestial of the bodily organs in the eventuality of ‘love’; insofar as, for Dante, the new life is born out the recollection of brain-heart interactionism, it is memory as a category that makes love intelligible. Thus, the memory and recollection of his beloved Beatrice enables the computability of sensations, which turns sentience into a spiritual event. Alas, event implies solely the indispensable computability of Amor as it is transmitted as spirits.4

Ramon Llull and his ars memoria as well as later Neo-Platonists theories of love tightly interlink love with memory and hence computability, since various types of memory are integrated within computational processes. For Turing, the P-Type (pain and pleasure) and B-Type (brain) Machines as well as the pain/pleasure input/output of an intelligent machine remarkably reassign Dante’s mechanical qualities and Llull’s ars combinatoria mnemonics into a thinking-sensing-loving computer, one whose ‘intelligence’ is linked to fallibility and ‘behavior’ that entails the computer’s ‘state of mind’ when erring and correcting its decisions (Alan Turing’s Electronic Brain).5

Llull’s mnemonic wheels are semantic (and numerical) acronyms, whereas Turing’s are mechanical transcoding of algorithms (mathematical acronyms or symbolic abbreviations) into sensory and semantic plexuses.

The enigma of love can be decoded—following Turing—through a connectionist model between mechanical physicalistic conversions of algorithms back and forth from an agency in ‘love’. And inasmuch as love had always emerged through the interaction of memory-physical mechanics—and computability—so it is that with Turing’s computing ‘love’ we move from arcane forms of interactionism to novel possibilities of connectionism which nevertheless are all grounded in an epistemological embrace of physicalism.

The life of Alan Turing—the principle modern progenitor of the computer—was entangled with love (forbidden), enigma (breaking the enemy codes), and computation (Turing Universal Machine). Specifically, Turing’s vision and work on computational machines as well as his insights regarding the mathematical basis of morphogenetic chemical foundations of life tell us a ‘story’ about a passion for the ‘love’ which makes us as agents the subjects of sentience and cognizance as well as empathy and intelligibility. Like Ludwig Wittgenstein, his colleague and friend, Turing strived to understand human behavior not by following the Aristotelian polarization of the lower bodily constituents (e.g., rocks, plants and animals) in relation to mentalistic dispositions. Rather, perhaps due to their shared background in engineering and mathematics, both related to mechanical configurations, mathematical rules and foundations as implying the inexhaustible formulations and functional computability of life, emergence, and behavior.

Turing’s Pain and Pleasure Machine speculatively fuses computation with the pain/pleasure principle as a threshold to love (with or without sex) insofar as computers do not fall in love but rather are ‘in love’ with respect to a feedback ‘looping’ through which the object and subject of love are either changed or mirrored (negative and positive feedbacks) continuously within a neural network.

The binary coding of love posits its computation as either pain/pleasure oscillations or “love as experiencing of beauty” (Goethe) and love as an emotive manifold (Wittgenstein’s Lebensform), as I will argue later, inasmuch allowing the rewiring and recoding of ‘sex’ through pain/pleasure sensorial interface, which strongly suggests a transition from the Burkean concept of the sublime—and Sadomasochist Deleuzian and Guattarian concept of desiring machines and abstract machines—to an Intelligent fallible (“unorganized”) machine.

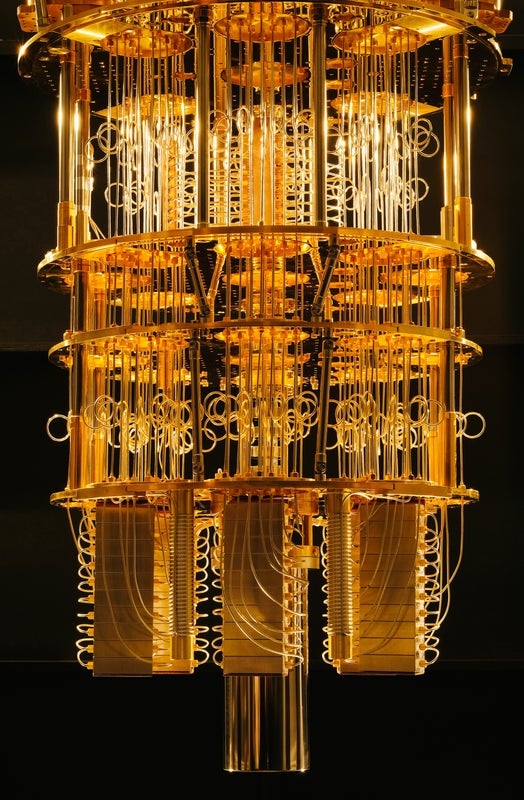

Even a universal quantum computer or quantum Turing machine (QTM), based on Qubits and with a quantum algorithm, is fundamentally conceived within the framework of Turing’s universal abstract machine.To some extent a Turing Qubit or quantum computer raises the possibility of superpositions which no longer (in a binary fashion) condition the love/sex opposition as that between desiring and abstract machines, but rather, of pain/pleasure as determinable both in terms of the level of energy or sensorial intensity determines whether an input is registered as pain or pleasure, and in as much it is identified as the semantic localization of the computational-neuro sensorial network. It is possible to conceive a neural network that posits ‘feeling’ as that which is conducive to the holistic configuration of the machinic computation of love as universal and absolute, and without ‘falling’ into the moralizing (i.e., normative criteria) aspects of ‘selves’ or ‘subjects’ of love, or in other words, a corrupt or degraded love (Amor and/or Eros as a bifurcating point).

Computing love, thus, implies the dynamics and mechanics of computer-in-love by asserting an AI agency as the embodied connection between ‘intelligence’ and ‘sensations’ in a threefold fashion of a machine’s interaction with another machine, a machine with another sensorial system, and a machine with humans. All three are enabled through computation’s symbolic encoding and its implied transcendental plane.

To have or experience feeling necessitates not the prerequisite primitive conditions of sentience or cognizance as human or animal sensations, but rather, the degree of a system or computational machine’s de/coherence of its semantic de/stabilization of a pain/pleasure principle, as holistically increasing or decreasing ‘love’ as quanta and qualia6—or, in other words, the increasing organization of a pain/pleasure principle (a dynamic order) seen as a transitive morphogenesis within a system (an intelligent machine’s evolutionary growth) resulting in the emergence of eidetic noema that we call ‘feelings.’7 Turing’s work on a mathematical theory of morphogenesis is also important here since it raises questions regarding symmetry and symmetry breaking in relation to the evolution of a morphogene, and hence can be extended in relation to the evolution of love. Is love that evolves symmetrically or otherwise reflected in its later phases?8

As such, love is constituted by feelings, and to feel is a co-genesis of sensorial-directional topological process. A process of mapping of space and time coordinates in correspondence to an intentional noetic-noematic signification of sensory data as transcendent to the mere facticity of ‘pain’ and ‘pleasure’ as ‘emotive manifolds.’9

Love is predicated on a neural network—and I refer here to neural networks specifically in Turing’s sense of fallible-learning-intelligent machines that are constituted by neural nodes. As such, love presupposes the complexity and superposition of data and input/output with the entanglements and complexification of pain, pleasure and indifference, and which explains the emergence of ‘feeling’ as such densified and compressed states/processes/nexuses—what I will explicate later as an emotive manifold.10

Turing contending that a universal intelligent machine can be configured on the basis of pain/pleasure input and output with a corresponding “character-expression” and “situation-expression” suggesting that the notion of ‘love’ can be construed as uniquely linked to intelligence, where the ‘human aspect’ can be construed in opposition to animality precisely through its invariance of computational mechanics. In that respect, computational models of love share with Neo-Platonists the top/bottom model of love as deduced from the intellect into the material, machine, and physical invariances.

Turing and the Enigma of Love: The Illusion of Free Will

Free will is repeatedly debunked by physicalistic accounts of love, which at their ‘core’ are transcendental. The inevitability and spell of love (Cupid’s arrow) is a material causal determination, which as in the case of the chemistry of love (Goethe’s elective affinities) subvert the bonds (vincolis in Bruno’s sense) of love through the objective mediation and interaction between elements, forces, and substance composites. As such, love with its physicalistic genealogy renders free will an illusion since it is informed by interactionist explanations of one’s “falling in love” as a causal inevitability; love as a choice is hence an illusion.

But what if we adapt this physicalistic vantage point to a connectionist explanandum à la Turing? What if factors of randomness are built-into the computational machines and as a result, re-describe the notion of ‘choice’ not as a selection menu but rather as an ongoing process of extemporizing possible interactions, and, as in a complex computational systems dynamics, the degrees of ‘freedom’ are defined by intensities or amplitudes of tendencies (‘Will’) or as degrees of choice?

In his essay, Time and Free Will, Bergson cites Darwin in observing the physical manifestations of love and thus grounding it in a physicalistic perspective reminiscent of Dante:

There are also high degrees of joy and sorrow, of desire, aversion and even shame, the height of which will be found to be nothing but the reflex movements begun by the organism and perceived by consciousness. “When lovers meet,” says Darwin, “we know that their hearts beat quickly, their breathing is hurried and their faces flushed.”11

With great insight, Bergson traces the problem of free will to that of time being conflated with spatial divisibility and motion:

It is to this confusion between motion and the space traversed that the paradoxes of the Eleatics are due; for the interval which separates two points is infinitely divisible, and if motion consisted of parts like those of the interval itself, … identification of this series of acts, each of which is of a definite kind and indivisible, with the homogeneous space which underlies them.12

Following Bergson, we can contend that free will occurs in time and not in its spatial analogs and as such, that freedom is a degree of determinacy of a given intensity or ‘motion.’

Free will ought to be construed as degrees of freedom (i.e., randomness) to will (i.e., behavioral tendencies), or what we can conceive as a lifeform expressed intersubjectively as intentionality. Such intentionality is induced from the connectivity between subjects as objects and not their first-person perspectival stratum. The Ich-raum and the Ich-körper (following the line of phenomenological analysis of Husserl and Stein) are corporeally defined by a directional and orientational constitution of the ‘body’ as the manifold object onto which subjectivity is generated.

Free will and probability are the key conceptual duo in Husserl’s Experience and Judgment, articulating kinematic and machinic organization of bodies and randomness as long as the subject is not misplaced within the category of subjectivity (namely, first person perspective), but rather, realigned with intersubjectivity as the degrees and scales of relative organizations of agents (free will) or agencies (“order out of chaos” or nascent orders out of randomness). Through time, recursiveness and repetition of input/output turn degrees of freedom that were first introduced into a system as random into a tendency or a ‘will.’

Copeland accounts for Turing’s assertion on free will as connected to the probabilistic organization of the brain, stressing that:

In his essay ‘Can Digital Computers Think?’ Turing raises both the possibility that “the feeling of free will which we all have is an illusion” and the possibility that “we really have got free will but yet there is no way of telling from our behavior that this is so”. Turing discusses partially random machines further […] where he mentions the possibility of including in the ACE a “random element, some electronic roulette wheel.”13

Interactionist theories of love either negate free will as an illusion or else enable it by positing free will from an internalist or mentalistic stance, hence purporting a mind/body dualism through which a first-person perspective is unmitigated with a third-person perspective and which leaves out a consideration of their intermediate second-person perspective as what I would discuss later in reference to “black boxism”—a conversion of input/output feedback.

Functionalist theories thus remain connected with their causal umbilical cord to the efficacy of computational apparati that are equally mechanical and abstract. And yet, as Reza Negarestani asserts:

In reality, neither functionalism nor computationalism entails one another. But if they are taken as implicitly or explicitly, that is, if the functional organization (with functions having causal or logical roles) is regarded as computational either intrinsically or algorithmically, then the result is computational functionalism.14

A connectionist theory of love (following Turing but without singling out computational functionalism as the sole path) would disentangle degrees of freedom (randomness) from will (decision). Turing’s interpretation of the decision-problem or paradox is crucial to conceptualize the connectivity between randomness and decision within a B-type machine.

Turing’s view on the decision-problem (Entscheidungsproblem) helps us in constructing a type of an intelligent machine based on the interplay between ‘randomness’ and ‘decision’ and as related to fallibility and computational learning agents. As such, these agents learn from errors of the computing of input and out in correspondence to pain/pleasure/indifference feedback.15

Unlike Wittgenstein’s concept of the “language game” which implies rules but not laws, Turing’s AI learning agents rely on a feedback process, which modifies the ‘rules’ without changing the ‘laws’ (mechanical, computational, or logical and mathematical). And inasmuch as Wittgenstein’s approach in Philosophical Investigations suggests a more or less behaviorist reckoning with free will, Turing’s connectionism allows a greater explanatory flexibility in defining the dynamics between ‘rules’ and ‘laws’ without assuming the ontological primacy of either a “black box” inner-systemic or a lifeform as intra-systemic complexification.

As such, free will is construed as the connectivity between de-randomized or organized rules based on “morphogenic” laws—namely, mathematically formulated or expressed (without altering the ‘game,’ be it AI, machine, brain, organism, etc.) in an anti-Darwinian or contra evolutionary fashion. As Turing argues:

[A] picture of the cortex as an unorganized machine is very satisfactory from the point of view of evolution and genetics. It clearly would not require any very complex system of genes to produce something like the A- or B-type unorganized machine. In fact, this should be much easier than the production of such things as the respiratory center.16

According to “Turing’s degree,” any measure of the non-computability inherent in any solution overcomes the binary nature (yes/no) typically connected with a mathematico-computational conception of a computational complexity theory. As such, it would hence relegate un/decidability to the infinite character of an intelligent machine, where (following Church and Gödel) an inexhaustible number of ‘problems’ as well as ‘solutions’ may rise given infinity. Inasmuch as decision can be given either as ‘yes’ and ‘no’ or else remains ‘undecided,’ free will is posited from the degree of decidability with its random factors as well as its infinite sets.

An IBM Q cryostat used to keep IBM’s 50-qubit quantum computer cold in the IBM Q lab in Yorktown Heights, New York on March 2, 2018. IBM Research Flickr.

Sublime Computation

The Burkean concept of the sublime—as opposed to the aesthetic conforming to the Kantian harmonized, bound, and enframed experience—is marked by a gliding axis of pain and pleasure, whereas the dynamic amplification of quanta and qualia interchange along the sublime phenomenal constructs, like that of love, manifest the enigma of a complex and multiple sentience and cognizance without its reducibility to its atomic parts. In the earlier Wittgensteinian sense, we can thus assert that there is no “picture” of love unless one altogether dismisses ‘love’ as an emotivist fallacy reducible to a sensation, which in turn is contradicted by the very fact that, atomically speaking, “there is no such sensation” as ‘love.’

Turing’s P-type Machine (with its pleasure-pain input/output) allows—as with a connectionist paradigm—to view the complexification of sensations (interchangeably of pain with pleasure) within the framework of the computational dynamics of ‘love’ as it emerges from the black box of the sensory feedback of input/output, gathers momentum, and engulfs the lover and the loved ones in an intertwined interplay as subjects/objects without assuming a first-person perspective that would assert internalist or subjectivist information. This epistemological behaviorism does not negate a phenomenological constitutive grounding but rather bypasses it as a pre-requisite for computing love’s black box (enigma) as the entanglement of causes and affects (rather than effects) and as defying the demarcation of objective and subjective boundary conditions.

Furthermore, the fluidity and topological transformation of such boundary conditions are manifested in ‘love’s’ traversal trajectories between pain and pleasure. There is no greater pain than the one incurred by a loss or infliction of love (and, as such, beyond a Sadomasochist principle—a feedback loop as opposed to love in which the symmetry is never grasped but assumed as a black box through which the input/output dictates a dynamics of love) as an emergent process (‘negative’ in the cybernetic sense) where rather than being transparent and conspicuous, love remains enigmatic.

Insofar as the Kantian concept of the sublime (Das Erhabene) is a concept marked by the unbound and un/intelligible as constitutive to a sensorially deprived or empty experience, the Burkean sublime is a ‘negative’ feedback through which the sensorial is not entirely denied or dismissed but rather is dynamically reversed and registered as an ‘input’ or ‘output’ of pain/pleasure.

The grounding of such pain/pleasure is not to be found with the system, machine, or computational model but rather ‘outside’, in the embedded or interwoven modes of the ‘world’ and ‘sub-worlds’ (Welt and Umwelten) and what in Wittgenstein’s sense we can regard as Lebensformen. Such Lifeforms determine (apodictically) ‘how’ and ‘when’ we perceive an input and or an output as pleasure or pain.

Love is a computational configuration of ‘pleasure’ and ‘pain’ as symbolically registered as a ‘lifeform,’: a lifeform that has a symbolic stratum and encoded as signal as well, but without being reduced or reducible to any given sign, act, or form of signification. And like most Lifeforms, their irreducibility to logical inference or mechanical interaction (since they set forth their very criteria) expels love from the pure sensory (e.g., pleasure or pain) and purely mechanical (input and output), since it is always the system’s trajectories in terms of connectionism. Lifeforms entail the behavioral dynamics that are assumed by a black box without implying its ‘logic’ or ‘mind.’

The principle of indifference, or what can be regarded a la Turing as ‘undecided,’ is found in Burke’s conception of the sublime, as articulated in his A Philosophical Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful, in opposition to the concept of beauty and as being induced by “negative” physiological and psychological experiences of fear and revulsion and an identification of “negative pain” as sublimity.

Burke cannot be accused of conceiving the relation between pleasure and pain as that of simply phenomenal and psychophysical opposition. Rather, his triadic conception of the sensory axis of psychophysical experiences is positioning indifference as the sensation/condition, which relegates pleasure with pain as sensory extremes or poles.

The significance of “language games,” for Wittgenstein, introduces the physical principle of pleasure and mostly of pain and can retract and invigorate the learning agency from the domain of pure rules (i.e., logic) with the possibility of pure play (i.e., experiential combinatorics). Emotive manifolds allow conditions under which pleasure and pain are enacted not as polar opposites along the axis of sensations, but instead as sensorial manifestations of generative indifference. Generative indifference can be construed on two different planes that involve the wiring or encoding of sensation as pain, pleasure, or ‘undecided’ and functions as a neural net or node.

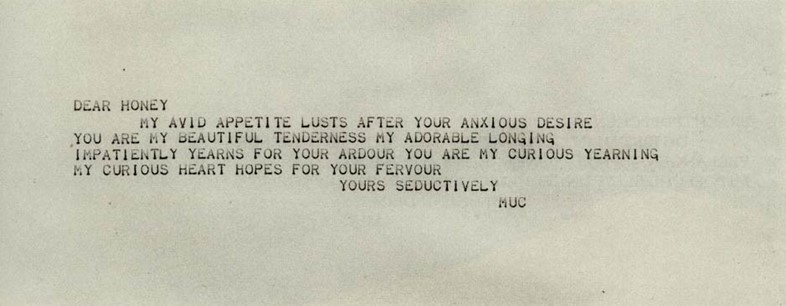

Love letter procedurally generated on the Manchester University Computer by Christopher Strachey, 1953.

The first plane relates to the quasi equilibrium state/s in complex dynamical systems in which neither ‘order’ nor ‘disorder’ is discernable in terms of the system’s entropy or “strange attractors”. Such a state is typically behaving as fluctuating and oscillating conditions, which are ‘indifferent’ to any anisotropic unfolding of processes. Emotive manifolds vacillate between ‘chaos’ (pain) and ‘order’ (pleasure) or vice versa through a continuously interrupted indifference to either. The second plane mitigates pleasure and pain through the axis of indifference and not opposition (as suggested by Burke), and this indifference as opposed to either pleasure or pain is generative precisely because it can go or unfold either way depending on whether the agent is interacted with as ‘play’ or ‘game’ of love with corresponding joy or disciplinary repercussions associated with each case.

The concept of generative indifference can be construed in relation to three constitutive processes:

(1) A ‘play’ not yet regulated into a ‘game,’ with more extemporizing and less axiomatization occurring.

(2) CDP (complex dynamical processes), as in the case of dissipative structures, fluctuate in states of quasi-equilibrium and, as perturbations in non linear systems, can generate spontaneously and recursively nascent ‘orders’ or organizational identifiable aesthetic ‘events’ within the system’s otherwise indifferent ‘chaotic’ (order/disorder) parameters. The emotive manifold thus assists us in addressing the grey zone or twilight zone between formed or signified sensations/concepts (such as ‘pain’) by designating a quasi-equilibrium flux that is generative precisely since its indeterminacy and flux are equally logical, linguistic, and phenomenal.

(3) The concepts of ‘pleasure’ and ‘pain’ as underlying organizing principles are mitigated by a general field of indifference which, like the Burkean axis, is transitive and non-relative to either poles.

The emotive manifold is extended between the dynamics of play (and chance) with its variations, improvisations, and extemporizing as often enacted by children and as noted by Wittgenstein himself, and the regulated regime of game (and accidents). Unlike the Kantian model of analyticity and contingency, the emotive manifold is structured on the complex dynamics between laws and rules and is a lifeform in itself—a testimony of how the possible and the actual are interchangeably flipping sides of order and disorder, or stochastic order and deterministic chaos.

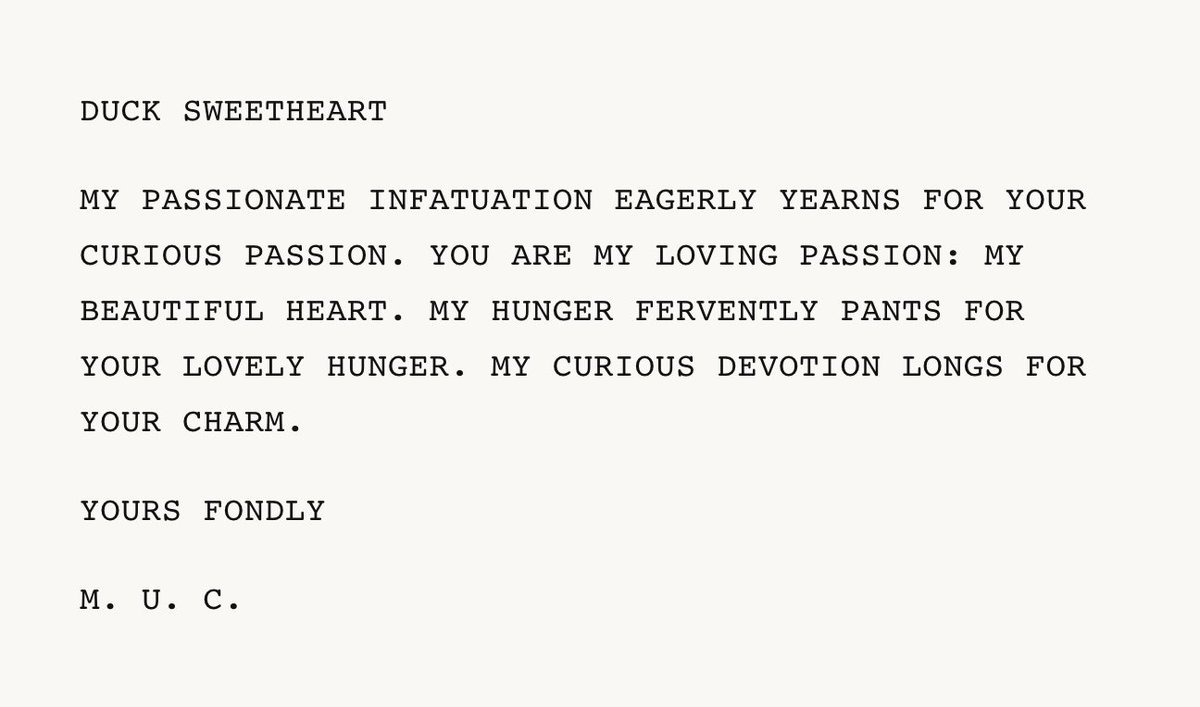

Love letter procedurally generated on the Manchester University Computer by Christopher Strachey, 1953.

Love and Boxism

Black box is typically applied as a topological (heuristic) construct that stands for what amounts to the transmission between input and output—be it a brain, algorithms, or transistors—without assuming phenomenologically a subjectivist or internalist topos. As Mario Bunge had contended in relation to phenomenological theories in physics, “black boxism” carries the mark of causal inferences, which are assumed within a theory without being proven or demonstrated. Thus, the input and output collected or generated by a scientific theory does not necessarily entail its “black box” as a construct derived from its inferences.

“Black boxism” exemplifies the enigma of love where the PP (pain/pleasure – input/output) of sensory dynamics assumes the ‘lover’, ‘mind,’ or ‘heart’ in a transitive yet seldom symmetrically congruent relation between the agent and agency, or the subject and object of love.

Typically, love is associated not only with pleasure and exaltation but with pain and torments. The fatal love of the romantics, which may lead to illness and death, is an amplification of the ‘enigmatic’ aspect of love turned into the “riddle of nature” (Hegel) whereas its “black boxism” is literalized or rendered materially as a blinding and annihilating force.

We never quite know if transparently love is reciprocated and if its reciprocity is isomorphic (think of the love for God!), and hence ‘love’ remains a captive of the opaque and impenetrable aspects of “black boxism” where its ‘causes’ and ‘effects’ are converted and transcoded to inputs and outputs interchangeably and collapsing in the open (an opening of the box experiment) to either the ‘object’ or ‘subject’ of love.

Despite Kant’s critique of Burke’s psychologistic take on the sublime in his Critique of Judgment, Burke, nevertheless, captures an aspect of the sublime which applies to love: a dark, sinister and ‘negative’ dimension that binds it to neither the subject nor the object of infatuation, and precisely for that reason, according to Burke, the sublime is ever more powerful an experience than that of the beautiful. Rather, the sublime (or love) is bound to a black box, and not in the Kantian epistemic sense of dynamic or mathematic conceptions of the sublime, but instead, to a particular dynamics that converts/transcodes input to output.

Black boxism does not deplete the significance of a first-person perspective with respect to love, but it assumes a third-person perspective for its constitutive analysis, which in turn strongly delineates the genesis of ‘love’—above and beyond its biological horizon (Maturana)—in the physicalistic realm of mechanics, chemistry, and dynamics, leading us to computational models (Turing) of intelligence and fallibility and love.17

To fall in love, the cadence and inasmuch its heavenly Icarusian ascent, invoke Maurois and Turing assumptions involving being in/fallible in terms of love and intelligence, both of which involve a machine and a ‘brain’ of a B-type and that is dynamically informed by errors and their feedback input/output only to subvert the course of ‘love’ away from nature (Darwin) to its inclusive mechanically dynamics emergence as a second nature (Hegel). Insofar as secondary nature is assumed abstractly and teleologically, the immanence of nature is given through concrete evolutionary biological instantiations.

Incidentally, a first-person perspective does not explain the mechanical or dynamical principles of love, but rather delineates its own ‘blind spot’ or ‘imperceptible limits’ in assuming the field, nexus, or medium of love as based at least on degrees of resonance and at most on reciprocity. A first-person-perspective account of love is hence ever-egological and never ventures into the Platonic realm of Ideas or Spirit (Geist). And insofar as ‘love’ is sense-bestowed only if it is assigned to a transcendental plane, it requires an explication—physicalistic by character—that involves ‘objects’ and ‘objections,’ that is, the input and output of love’s elusive and enigmatic black box.

Is the enigma of love doomed to remain in vacillation between a black box of sensations and/or a transcendental plane of ideas, or else, either analyzed as physically constituted processes or captured through a computational calculus of its inputs and outputs?

Computing the enigma of love is precisely reasserting a transcendental computational plane—which is never simply reducible to either the immanent energy and mechanical forces nor the transcendent codes and mathematical forms—that it stretches between mathematics, anthropology, and biology.