Speakers

Andrée Ehresmann (mathematician) Franck Jedrzejewski (philosopher, mathematician, musicologist) Frederik Stjernfelt (philosopher) Olivia Lucca Fraser (philosopher, programmer) Giuseppe Longo (mathematician, logician, epistemologist) Mathias Béjean (designer)

Participants

Lendl Barcelos (philosopher and sound artist), Mathias Béjean (researcher), Katrina Burch (researcher), Étienne Chambaud (artist), Valeria Giardino (philosopher), Matt Hare (philosopher), Sonia de Jager (researcher), Margarida Mendes (curator), Patricia Reed (artist, writer), Olivier Surel (philosopher), Tzuchien Tho (researcher), Max Turnheim (architect)

Abstracts

Andrée Ehresmann (with Mathias Béjean)

The Glass Bead Game Revisited: Weaving Emergent Dynamics with the MES Methodology

In Hermann Hesse’s book, the Glass Bead Game constructs “a kind of universal language” based on interrelations between different disciplines, the aim being a synthesis of all the arts and sciences. The game is not entirely, nor even consistently, described, thus opening to several interpretations: is it reduced to an intricate combinatory game searching for interactions between beads of established knowledge, or could it be extended for leading to innovative interdisciplinary research? It is the question we are going to examine.

To this end, we will consider the 25 years development of the MES methodology (cf. Memory Evolutive Systems, A. Ehresmann and J.-P. Vanbremeersch, 2007) to try to play a revisited “glass bead game” aiming at synthesizing the main characteristics of living systems, be they biological, cognitive, social or cultural. Based on a ‘dynamic’ category theory, MES models autonomous multi-scale evolutionary systems which evolve through successive complexification processes — adding, suppressing or binding components. The global dynamic weaves local operative dynamics, whose interactions are mediated by a flexible and plastic central memory developing over time.

One main result (Emergence Theorem) shows that the existence of multifaceted components (“Multiplicity Principle”) is a necessary condition for the emergence of components of increasing complexity orders, whose interrelations (“complex links”) are not reducible to a simple combination of links between their components. Applied to MENS (a MES representing the neural-mental-cognitive system), it explains the emergence of higher cognitive processes up to anticipation and creativity through the development of a higher Archetypal Core. Recently this has been extended to collective action, in particular to innovative design.

Conclusion: As long as the Glass Bead Game is played with rigid glass beads representing invariant structures or pieces of knowledge, it cannot deal with “becoming”, thus at most allowing for “combinatory” and “exploratory” creativity in Boden’s sense. To model “transformational” creativity – e.g. understanding how properly new rules (complex links) could emerge – the beads should be multifaceted, presenting different facets depending on context. These beads should have some plasticity and eventually disappear over time (e.g. to account for evolving knowledge).

Olivia Lucca Fraser

Artificial Intelligence in the Age of Sexual Reproduction: Some Sketches for Xenofeminsm

The notion of artificial general intelligence has taken on an almost mythic significance in accelerationist discourse, both left and right. I will try to analyse and plot this notion’s political coordinates, in a space that has, with somewhat different and sometimes conflicting ends, been mapped out by cyberfeminist research (by Alison Adam and Sarah Kember, for instance). The idea that artificial intelligence seems to crystallize, for many accelerationists, is something like an “emancipation of intelligence”, as Nick Land once put it. The forking of accelerationism into the left and right spectra can be seen as so many ways of articulating this idea and forging it into a programme: whether in the form of a neoreactionary demand for private exit (AGI as a line of flight), or the form of a cybersocialist push towards the rational social cognition (AGI as Geist).

The question for today, though, is: what should this idea – an emancipation of intelligence as crystallized in the notion of AGI – mean for feminism? How should feminism orient itself with respect to this idea? Cyberfeminism’s exploratory critiques of AI research and development (Alison Adam, Sarah Kember) are crucial in helping us get our bearings here, but the long game, the end we have in sight, is the one set in Shulamith Firestone’s searing manifesto of 1970, The Dialectic of Sex. There, she draws the skeleton of an uncompromisingly promethean feminism, which hinges on a strict normative antinaturalism: “Nature” shall no longer be a refuge of injustice, or a basis for any political justification whatsoever.

The emancipation of intelligence, for Xenofeminism, is continuous with the project of the enlightenment, understood as a thoroughgoing desacralization of nature, which itself is inseparable from a long-term project of gender abolitionism: the destruction of sexual difference’s political significance. This is the endgame xenofeminism has in sight, and the keystone joining cyberfeminist and transfeminist concerns with Firestone’s unrelenting radicalism. This presentation will try to lay some of the groundwork for these interconnected projects.

Martin Holbraad

Anthropology, Metaphysics, Art: Ethnographic Aporia at the Limit

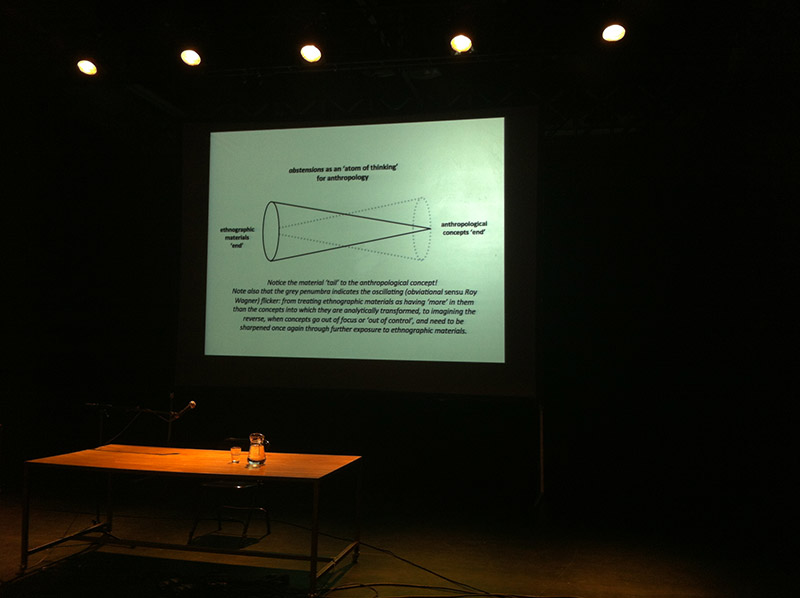

One can think of the particular turn of thinking we associate with anthropology as a calibration of two scales of alterity: one that plots difference on geo-cultural coordinates, from one society to another, and one that measures distances on the terrain of the imagination, from thought to thought. Anthropologists translate ethnographic alterities into intensities of argument, transfiguring the aporia of ethnographic ‘culture shock’ in the activity of thinking new thoughts. If metaphysics is par excellence devoted to thinking new thoughts, then anthropology conceived in this way is a royal road to it. One might even say that anthropology is hyper-metaphysical, inasmuch as its constitutive investment in alterity renders novelty of thinking as a kind of methodological necessity: the ‘meta’ of metaphysics must, by disciplinary exigency, also be ‘alter’, which is to say constitutively different, new.

This paper seeks to address the complaint that this vision of anthropology as ‘alterphysics’ does not quite live up to its promise in practice. Even when looking at the work of anthropologists who most deliberately ascribe to versions of the alterphysical project, at a certain level of analytical abstraction one tends to find a rather similar-looking set of ideas being (re-)generated with reference to ethnographic settings as different from each other as ceremonial gift exchange in Papua New Guinea, Mongolian shamanism, Japanese finance, Afro-Cuban divination, Amazonian hunting, European laboratory science, West African political violence, and so on: relationism, ontological transformation, mutual constitution, self-differentiation, multiplicity, process, becoming, non-humanism, cyborgs, the post-, the para-, the off-, the exo-, the minor. Indeed, these kindred ideas are typically not a million miles away from the conceptual currencies of certain strands of contemporary social theory, if not metaphysics – often the trendier ones. So how aporetic exactly, goes the complaint, are ethnographic exposures that tend so typically to issue in one version or other of, say, relationism? Taking this complaint as the single-most urgent challenge to the discipline of anthropology at present, this paper seeks to set out the coordinates within which different responses to it might be developed, and assess their chances of succeeding. In this connection, with reference to Lévi-Strauss’s idiosyncratic characterisation of art as a manner of allowing ‘the necessary’ to be revealed through ‘the contingent’, I end with the suggestion that anthropology’s distinctive claim to creativity may be cast as an inversion of art – a matter of allowing the contingent (i.e. ethnography) to be revealed through the necessary (i.e. analytical conceptualizations).

Franck Jedrzejewski

Ontological Fields: A Categorification of Space

We live in a world of fields – mathematical fields, scalar or tensor fields, electric fields or the Earth’s magnetic field – that keeps us bolted to the ground in complete indifference. In this lecture, I would like to show that the very existence of things is also a question of fields that I would like to qualify as ontological. These fields which induce appearances are responsible for the mutability of things and for the topology of multiple and heterogeneous sites that we develop today, such as the multiverse and pluriverse. I will illustrate my points with several examples, and show that to grasp these fields and the real in both its actual and virtual components, diagrammatic thought offers a suitable solution – as the diagram has a machinic and rhizomatic generosity that structure does not have. Finally, I will look at how the concept of field is a “categorification” of space – a concept I borrow from category theory in mathematics – and clarify what “to categorify” means in terms of methodology.

Frederik Stjernfelt

Diagrammatical Reasoning and Natural Propositions

The talk will present Peirce’s notion of diagrammatical reasoning. The core idea is that all deductive reasoning takes place by means of diagrams, explicitly or implicitly. Everyday examples include the use of maps, schemata, charts, pictures, gestures, language; scientific examples include reasoning with specially constructed diagrams, algebras, formalisms, etc. An important implication is that reasoning also involves a perceptual-observational aspect. Reasoning takes you from one proposition to another – so another implication is that diagrams and pictures may be used in the expression of propositions. Peirce’s functional definition of propositions thus extend their scope beyond human language, to non-linguistic semiotics as well as animal communication.

Giuseppe Longo

The constitution of Meaning: From Mathematical Structures to Organisms (E Ritorno)

Mathematics delineates the contours of the objects of the world, cuts them from their background, structures them with strong and stable physico-mathematical meanings. This historical constitution of the meaning of the inert has limits with regard to the description of living processes; the informational alternative diverts the understanding of biology into a meaningless dissipation of the organism, a partially programmed bag of molecules. The search for the organicity of knowledge and of the object of knowledge is the challenge that confronts us, especially with regards to the new interactions we have with the ecosystem. What interface between disciplines can contribute to this research program for a meaningful unity yet to be constructed, with the world?

Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game (1943) imagined a peculiar society set some five hundred years in the future, in which Castalia, a province of central Europe, is entirely designated as a place for the pursuit of pure knowledge. In this cloistered setting cut off from the world and its historical and political vicissitudes, the monastic inhabitants of Castalia, unencumbered by technological or economic concerns, are free to develop obscure objects of enquiry devoid of practical implications in the world extending beyond its dusty halls.

The apex of this ineffectual scholarly order is the mastery of a complex interdisciplinary game that synthesizes all forms of knowledge, in which musical motifs, philosophical propositions and scientific formulae all occupy the same rarefied epistemic space.

Castalia is an equivocal image: at once a hyperbolic caricature of Enlightenment reason’s pretensions to the autonomy, neutrality and normative objectivity of knowledge; and at the same time an idyllic respite from the political, technical and socio-economical embodiment of such forms of knowledge, whose dramatic consequences were all too evident in the horrors of industrial warfare surrounding Hesse. Castalia figures a conception of logic in which the synthesis of knowledge is achieved at the cost of its seclusion from the world, and the global structure of thought remains unchanged by its own actions.

The modern institution of art as a space of exceptionality prolongs and dramatizes this equivocal construction. Considered in excess and in exception to rational operations, art has produced forms of mediation and synthesis at the price of their operative inconsequentiality. This script of exceptionality has been left intact in the postmodern ‘expanded field’ of art. The truth content or value of art thus appears caught in a vortex of social relativism in which all foundations are considered lost, and in which a simulacral play of mirrors swarms out and distorts all particularity or universality.

The relativistic critique of rationality has revealed the normative structures that these equivocal images repressed. But it has also caricatured rationality, identifying it with fixed ontologies and tautological axiomatic foundations. Following this critique, the hierarchical privilege historically accorded to the universal over the particulars it subsumes is overturned, so that it is difference that prevails, and that is taken to undermine the objectivity of rational discourse.

On the contrary, we may say that reason is primarily socially embodied in practical and conceptual discourses, and that formal logics should be seen as the explicitation of the logical rules that are implicit in everyday behaviour. Logic now pervades our lives in another way, largely opaque to common understanding, in the computer scientific development of diverse automated algorithmic systems. In this fast evolution of computational technologies, it becomes again essential to pose questions regarding ontology, rationality, and normativity; as well as to explore again the dialectic between figures and backgrounds, particulars and universals, authority and responsibility.

History did not end, and in its background scientific reason has continued to irreversibly alter the field of knowledge. Mathematics and logic developed undeterred by the loss of foundations, indeed because of this unmooring. The same year The Glass Bead Game was published, two mathematicians (Samuel Eilenberg and Saunders Mac Lane) undertook the development of transit rules that would lead to the basis of category theory, and opened the possibility for truly synthetic forms of reasoning across many other disparate systems. Initially developed as a mathematical paradigm that could act as a universal medium facilitating transits between increasingly specialised mathematical languages, category theory has recently started to be applied in different fields, notably in systems biology, and in computer science, where it develops as an alternative to object oriented programming. The fundamental unit of interest for category theory is not the object but the morphism, or transformation, according to which the dynamics of an object, system or process may be defined, by showing their variables and invariants under transformation. This radically alters the conceptualization of particularity and universality, since there is a rigorous mathematical language that allows for their redescription in terms of locality and globality, yielding the possibility of a relativist yet absolute knowledge.

Morphing Castalia is an investigation of this model in which thinking transforms thought. The issue is not to rebuild the old foundationalist dream of a completed universal language; neither to reconduct the standard critique of rationality, but to construct the conditions for universal transits transforming the sites between which they operate. Looking for the possibility to engage with these sites in ways that would not privilege their local inscription over their global resonance, Glass Bead started its inquiry in April 2014 in New York by focusing on navigation and gestures as concepts through which it can be possible to operate these transits. At Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers this fall, Glass Bead pursues this investigation by exploring how such transits could be developed further by examining the ways in which synthetic approaches that have emerged in contemporary mathematics can be seen to affect cultural, biological, technological, and political landscapes.

The week will comprise three evenings of public lectures, each followed the next day by a private workshop leading to an interview of the speakers dedicated to the crafting of transits between their respective practices.